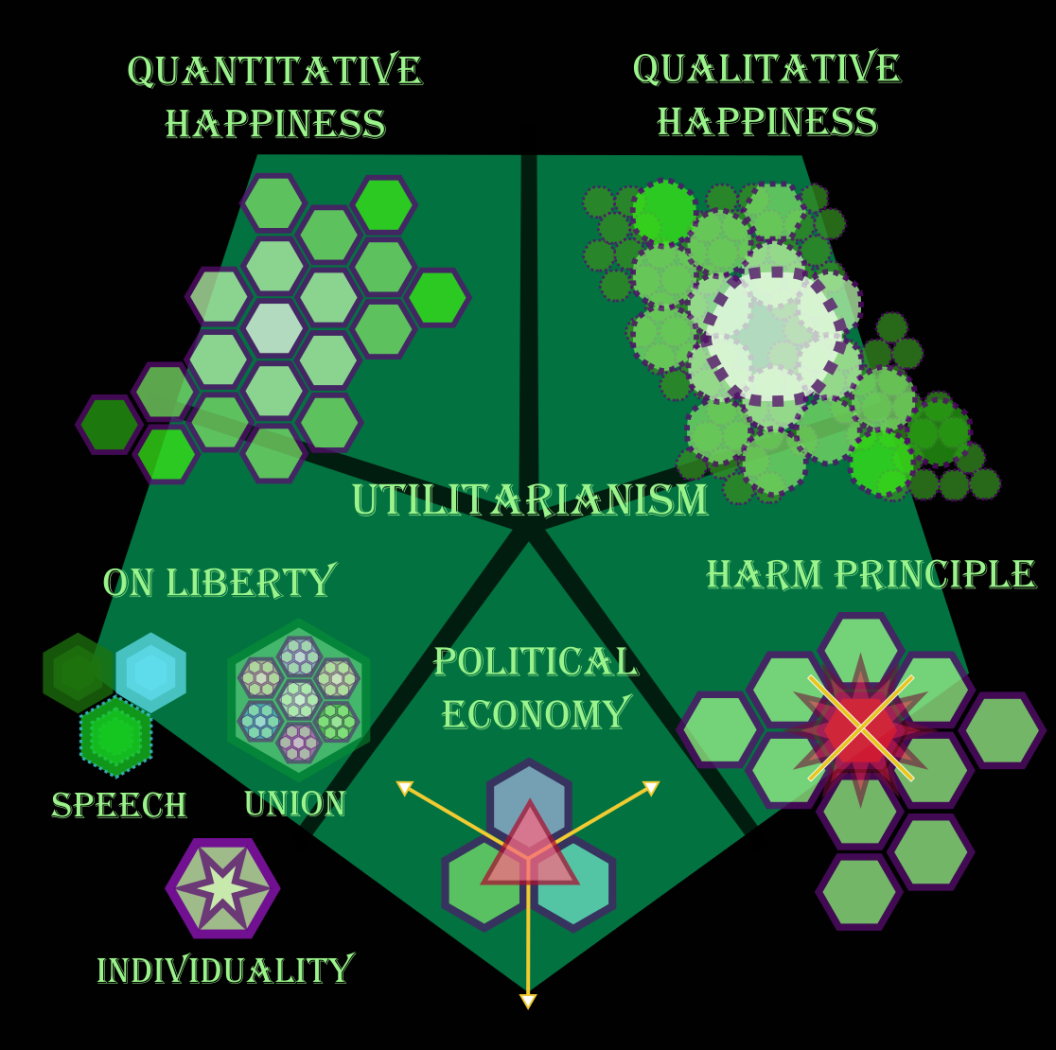

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist approach to ethics that attempts to objectivize worth in terms of “utility” (happiness, negation of suffering, pleasure) rather than adherence to universalizing laws (deontology) and motives (virtue-ethics). Classical utilitarianism adopts the Epicurean valuation of pleasure as a fundamental principle sought by all members of a society; pain, aside from masochist/sadist dichotomies, constitutes the opposite or undesirable. The English combined these concepts with the empiricst/Humean principles of cause & effects where the latter is considered social utility.

The two major proponents of this school of thought, Bentham and Mill, equate pleasure with happiness but differ as to how social utility is measured. Bentham quantified the “greatest happiness for the greatest number” as the determination of right/wrong; Mill qualified the determination as the “greatest aggregate happiness among sentient beings” which ranked happiness according to intellectual/moral pursuits higher than that of the physical/body. Mill justifies the assertion with the claim that one would choose the former over the latter if both are experienced; this can be be obviously attacked on the grounds of cognitive biases / variations of temperaments in later history. Intrinsic or not, the valuation implies an inequality amongst “moral goods” and subsequently the individuals who pursue them; such effects would be case-sensitive in the sense that worth is never absolute (for example, fur coat production in Siberia would be worth more than production in Egypt). Thus, codifying such a book of laws on social utility tends to intermingle many practical spheres such as economics and politics.

Liberty is a central trade-off one makes in the pursuit of personal happiness and the concern with social utility; the “tyranny of the majority” may decree a law that increases their sense of securities whilst marginalizing your freedom (for example, the negation of liberty can be realized in incarceration). The limits of such acts are bounded by the “harm principle” which circumscribes all coercion by the state on an individual to actions that would prevent harm to its other members; one’s incarceration is evaluated by your danger to the public. As for the positive definition of liberty, Mill makes three claims (freedom of speech, taste, and union). Freedom of opinion (truth, half-truths, and falsehoods) in valued in so much that their expressions are necessary in the production of effects to which their moral statuses can be continually re-evaluated. Taste or individuality appeals to the biased ranking of different pleasures which must be experienced to be apprehended. Union is encouraged for the many can obtain greater pleasure for the whole than otherwise the singleton (for example, the shift from artisan crafts to mass-industrialization produces greater material wealth, the social costs are another story). Co-operatives are encouraged as profit-sharing increases the awareness of the common goods (satisfaction from participation with the whole) that counteracts the growing alienation of industrialized labor. Taxation becomes an instrument by the state to evaluate and manipulate social good.