1870 – Artificial Man – Orin Vasta (Swedish)

Source: The Daily Telegraph Harrisburg, PA.29 Dec 1870

A NEW ADAM IN SWEDEN. Curious Story from a Swedish Paper—

How a Man was Made—What a New Being Thought and Felt—How He Acquired Ideas, etc., etc., etc.

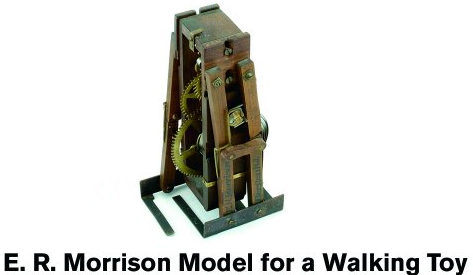

The New York World says: A Swedish paper makes the seemingly preposterous assertion that a scientific gentleman of Stockholm has succeeded in fabricating a man—not a "steam man," nor a man who goes by clock-work or springs, but a veritable man—whose flesh is such as is common to the genus homo, whose bones are filled with true marrow; who, if he does not think, talks as if he did; whose hair and nails grow; who breathes, lives, moves, and has his being, and in all particulars is such as he would have been had he been turned out in nature's workshop, and not in that of Orin Vasta. To be sure there are necessarily minor points of difference between this product of assisted nature and the ordinary products of unassisted nature. The being—for it is hardly right to call him a man, after all—has, of course, no recollections of childhood, or even of his brother, "the insensible rock and sluggish clod," with whom, twenty years ago, he was intimately acquainted. He has no past extending further back than three years, and as little understands the process of his fabrication as does the new-born child, and he came into conscious existence in a second, or even less, by a period corresponding with the rate at which the nerve force travels. He was born a full man, with a brain pan as capable of producing mature thought when material for thinking was supplied, as is an ordinary man of 25 years of age It took him only six months to learn to speak the Swedish language with tolerable ease, and then he was able to tell the impression made upon him by his existence, so accurate was his memory. By no means would we vouch for the truth of all this, but the story is good enough to be repeated.

The way in which the monster was constructed is peculiar. Frankenstein was absolutely nothing compared with him. He was not made of wood and iron, but of various pieces of dead human bodies, carefully selected, preserved, prepared and adjusted in such a way that after the head was put on the shoulders, and the two pieces of spinal column joined at the neck, in an instant the nervous machinery acted, the heart palpitated, the lungs inhaled and exhaled air, the eyes opened, color came into the hitherto livid face, and all the processes of life began; the theory of this being that, as no two bodies are ever in actual contact, the molecules of man's body are not. Vital processes do not, therefore, need actual contact of particles in which they appear, there is, therefore, no necessary interrelation between them, and if by compression they can be forced to within the same distances from each other which they have in life, life must ensue when, by connecting the spinal column with the brain, transmission of nerve force becomes possible.

Hereditary transmission of mental and physical qualities is impossible in a being thus constructed; for, as there is no germ, so there is no development of it; the being is but a composition of what is commonly called "dead matter." To all intents and purposes such a being is the primitive man of whom the world has heard so much, and therefore is fine material for psychological study.

After twenty years passed in hitherto fruitless experiments, it may be believed that Orin Vasta was excited when, all things prepared for the calling into being of a monster, he proceeded with the experimentum crucis of joining the brain and the spinal marrow. To say that he was appalled by what he instantly saw is not to say an incredible thing, and, in very fright he fell to the floor, whereupon the newly created being did the same thing; but, when Orin arose, his creature lay still, for the very simple reason that it is very easy to fall but not to rise again till one has found out how to do so. But the fabricator helped his newly made friend to rise, and seated him in a chair. Whereupon all sorts of emotions were expressed in the man's face at what must have seemed to him a strange doubling and cracking of himself, but in reality, as he afterwards explained, he had no such thoughts at all, but was merely a curious machine in which emotions were expressed in the face because of reflex action of the nervous system. This is a curious point, for during all the time which intervened between his creation and the development of speech in him he says he neither felt joy nor sorrow, pain nor satisfaction, although be would often be seen to weep and laugh and express all emotions and passions as a human being expresses them. If struck he would cry out and pucker up his face as an infant does, but has afterwards remembered how he felt at such moments, and could relate his thoughts; of course his experience is valuable, where a child's cannot be obtained since the first two or three years of man's ordinary life are utterly forgotten and lost. This singular being said that when he was struck he knew it merely because he saw it and experienced a new sensation in his head, and which he did not refer to the place smitten.

He had no desire to pucker up his face and cry, nor did he know that he did so till another different sensation which he felt in his ears seemed to set his head all in a whirl, one sensation begetting another until at last he thought that his head was all there was—that the room and his fabricator were all in it, and acting there as one. In other words, he was a sort of idealist, getting the universe under his own hat. Could he have expressed himself in philosophical language lie would not have said with Hume, that ideas and impressions were all that existed, but with some Germans, that ideas are all. But, to do him justice, he did not remain long in this condition of mind, for when his fabricator made him walk he obtained an idea of locality, and consequently of something that was not he, thereby making a great stride. But yet a more singular phenomenon than even these was noticed and afterwards interpreted by him. When he began to think he was conscious of an entirely new cerebral sensation, of disintegration of some fine substance within his head; he knew that this disintegration occasioned his thought and not vice versa. On this principle he afterward explained the well-known fact that in mental science, called the association of ideas, since mechanical action among molecules cannot but result in other and connected motions, and hence, if their product be ideas, these must always seem and actually be connected, while on no hypothesis except this is that remarkable fact explicable.

As time went on and the man had become gradually separated from his notion that he was all that existed, a feeling of awe and reverence sprung up within him for Vasta, whom naturally enough he called his master, and whom he considered a superior being, inasmuch as he felt himself in his power. He would pray that he might see his face always, for he loved him. To try an experiment Vasta withheld food from his creature for a day, and when asked for it took it from his pocket and bestowed it upon the poor fellow, who thenceforth for some time begged him night and morning not to withhold food from him. Afterward Vasta discovered that the man had formulated a prayer in which he, Vasta, was called the "Bread giver," and, merely from philanthropic motives, he dispelled this illusion, as he knew that its inevitable result would be to make the man very lazy. At first he had no idea of size, solidity, perspective or the ordinary properties of matter; but, when taught geometry, made most rapid progress, and when told one day that a straight line was the shortest distance between two points, astonished his master by saying: "No; a line is not distance at all ; a straight line is the shortest line between two points." He looked at all things in the most matter-of-fact way, but accounted for them in the most whimsical. There was, according to him, a "goodness" that made things good, an "evil principle" that made them bad, a "beauty" that made them beautiful, an "intellect" that made his master wise, and a "chairness" or "boxness" that made things chairs and boxes.

But as he became more conversant with nature these opinions faded away. Taken from his room into the streets of Stockholm, he saw men like Vasta, he saw houses and strange animals, and these set him to thinking, but when he went into the woods and fields and saw how plants and animals grew and the conditions of their existence, his views changed entirely. Vasta was no longer a god, but a man like himself. It was in the woods that the manner in which he was brought into conscious life was explained to him; how he was like other men in that every particle of his body was at first taken from his ancestors—if the dead bodies from which he was made can be called by so sacred a name—but that he differed from others merely in the fact that he was the result of a great scientific experiment, and had been produced merely for scientific purposes. "You see," said Vasta, "evidence of design in every part of the body; see how particular I was to put your eyes in your head instead of in your heels." "But why,"

was he answer, "did you not place them on long flexible protuberances in my forehead, so that I might have seen

in all directions without changing my position?" "Ah," said the old man, smiling benevolently; "had I done so how could you have worn a hat? In other words, how could you have been a social being ? Socially, it is as necessary to wear a hat as to have a moral nature." "But why not give me more hands with which better to earn a living and pursue science, to which I devote my life?"

Again the old man smiled. "Political economy would not stand it—it would have taken all your earnings to supply yourself with gloves, and thereby the mass of men would suffer, for nature has so arranged matters that in the universe there can be at any given time only gloves enough to supply the actual and ordinary number of hands." And so at every turn was this strange being taught by the philosopher who had only skill enough to make him, and in the end to leave him to shift for himself.