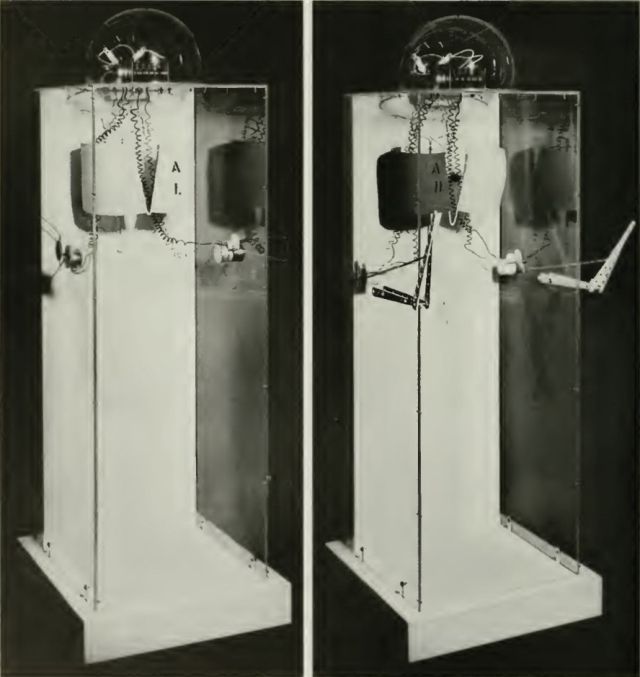

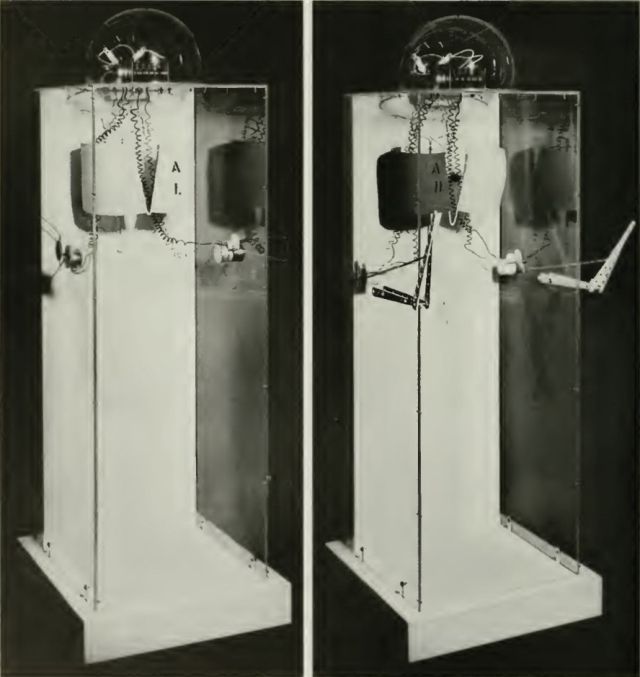

Anthropomorphicals I and II. 1964. Plexiglass and Aluminum. 65in. x 20in. x 24in. Richard Feigen Gallery, New York. 1965.

Source: Beyond Modern Sculpture – Jack Burnham 1968

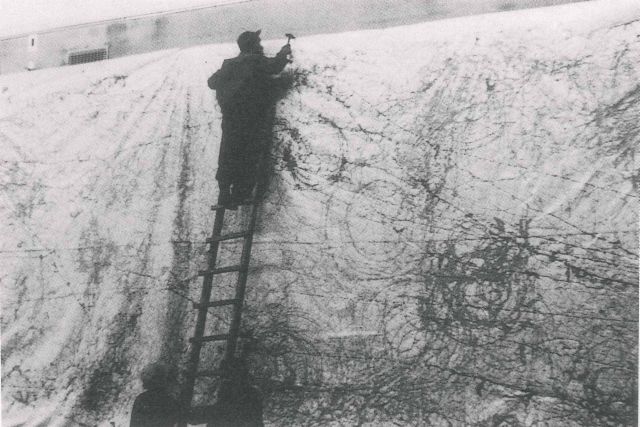

It would be misleading to classify [Hans] Haacke as an artist primarily devoted to applying cybernetic principles to mechanical artifacts; rather his interests are in those cyclical processes which manifest evidences of natural feedback and equilibrium. One might call this an environmental systems philosophy, one that has little to do with practical or theoretical science. Instead it reveals a keenly sensual attitude toward the most ephemeral phenomena.

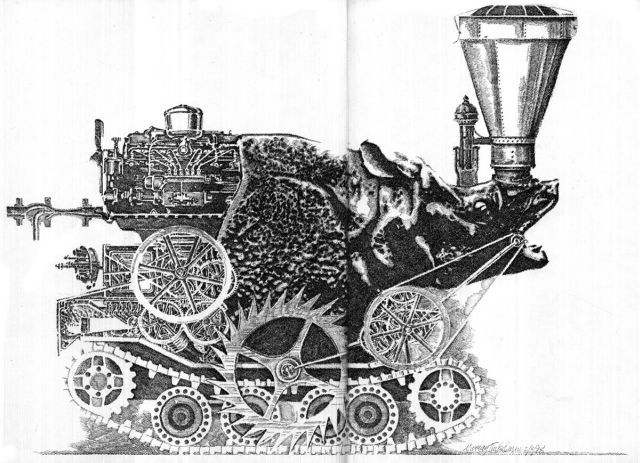

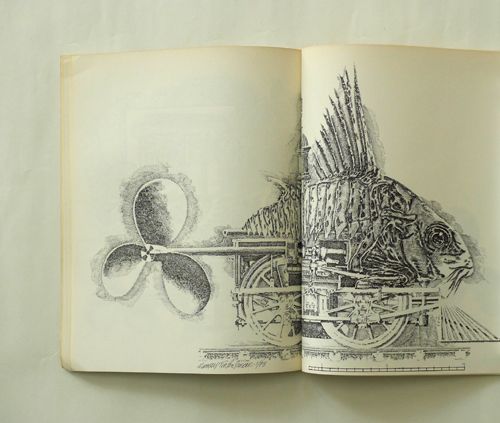

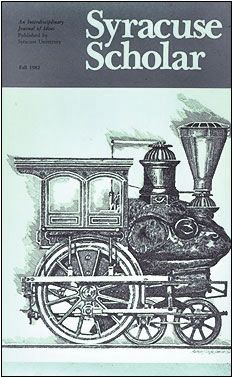

Clearly in opposition to Haacke's position is the Chilean presently living in New York City, Enrique Castro-Cid. The early drawings of Castro-Cid demonstrate a strong awareness of cybernetics as it is beginning to affect our notions of human physiology. These working drawings progressively substitute machine components for their anatomical equivalents. It is evident from the author's conversation with the artist that Castro-Cid has read deeply in the literature of mechanical evolution and the mind-body problem of classical philosophy. He senses that the possibilities of man-machine interaction are richer than ever before. Thus, his newer constructions depend more on this awareness and less on prevailing tastes in sculpture.

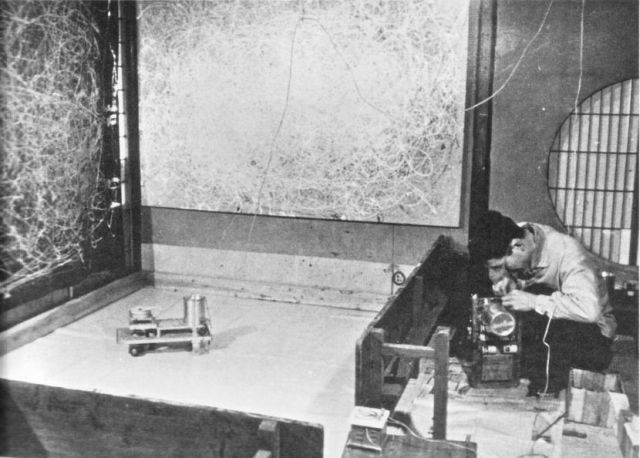

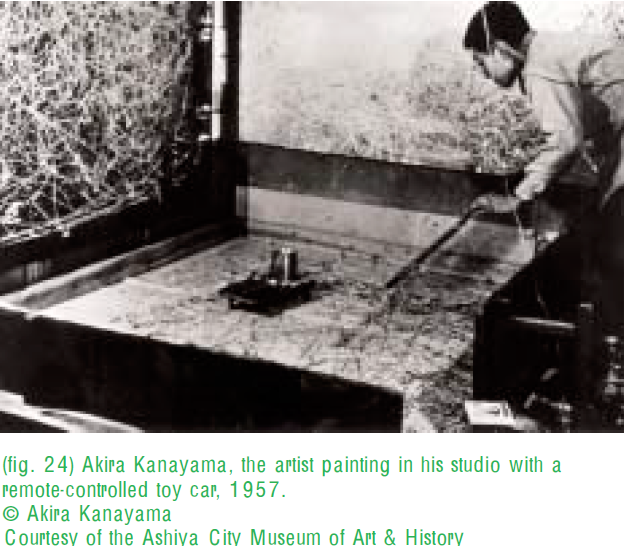

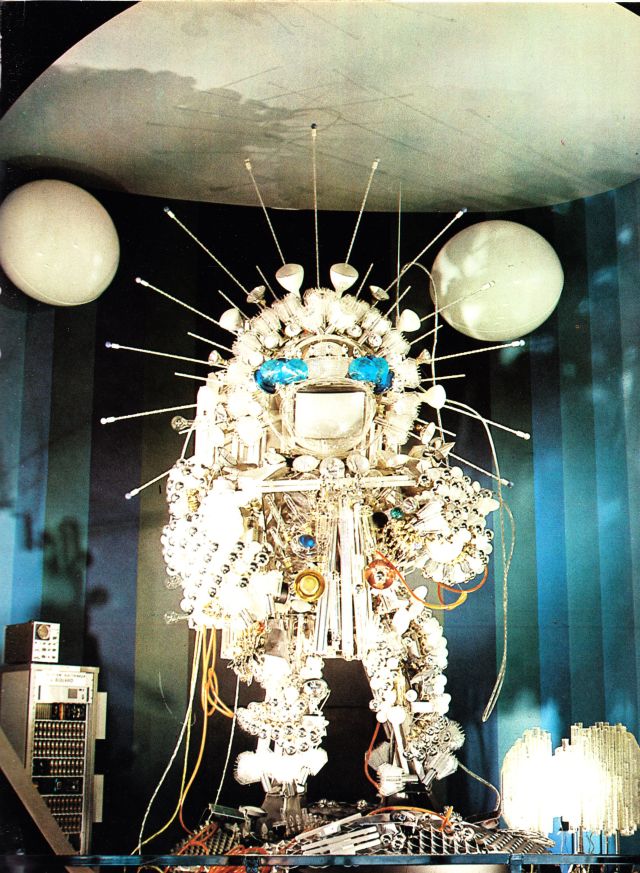

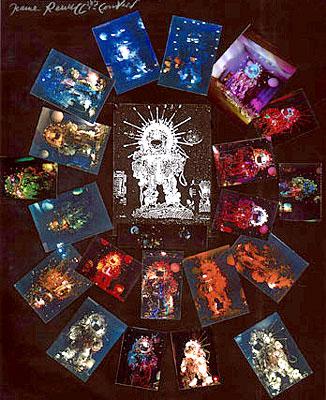

Since Castro-Cid's first robot exhibition in 1965, the artist has moved toward a more sophisticated awareness of man-machine interactions, in which anthropomorphism plays a diminishing role. The early robots (FIG. 126) are interesting for their painful sterility : no longer the clanking metallic beasts of the 1920's, these are more akin to humans divested of their corporeal form, mere brains placed in bell jars with appropriate electrodes inserted, sending commands to mechanical limbs. This contemporary electronic man is encased antiseptically in a clear plastic enclosure ; a vestigial anatomy drawn on the background hints faintly at a once biological life. Wiring and small components take the place of tendons and blood. Anthropomorphic I (1964), while suggesting the lapidary effect of a micro "mechanical brain," is technologically an unartful assemblage of synchron timing motors, a set of mechanical relays and a handful of light bulbs—all used to terrifying effect. But, reduced to its functional definition, this machine has none of the goal-seeking, self-stabilizing ability of even such relatively simple animals as Grey Walter's Machina speculatrix; it is, indeed, a mock robot.

Lately Castro-Cid's energies have gravitated toward a mode of sculpture which could be termed "cybernetic games." These are imposing, boxlike systems sometimes powered by air jets which keep plastic spheres moving within a defined cycle of positions. The trajectories of these bouncing balls are limited but appear to be random. There is a kind of ultra-precision to these constructions which implies more ultimate purpose than that invested in most New Tendency kinetic works ; they simulate the precise, instantaneous technology of a computer system in which playfulness is merely an aspect of some greater hidden function. The poetic imprecision of these games as On and Off—exists in the fact that they imitate a level of technology which they have little hope of duplicating. On the white surface of the compressed air sculptures are painted green areas which suggest different functions. The chasses of the games are extended into nonpurposeful shapes which contains no interior equipment.

What electromechanical components (photocells, electromagnets, air compressors and film projectors) Castro-Cid does use are invariably endowed with a certain forbidding and brittle austerity. Here the motion-picture form becomes the means for projecting a changing image with more substance than the imposing chassis housing it. While the chances for man-machine interaction often remain restricted with these sculptures, their real purpose, in terms of future art, is apparent : the joining of dissimilar systems into playful semi-automatic games in which the human operator can be seduced by an element of unpredictability while charged with the impression of strong purpose. In terms of their psychic complexity these works may appear to be trivial, but as a means of introducing ideas for reshaping the world they transcend the single-purpose machines of Kinetic Art and move beyond the limitations of scientific Constructivism.

It may be argued, justifiably, that modes of art do not transcend each other; they simply are. Yet a fundamental quality of art which has become possessed by technology is its tendency to follow the ascending spiral of sophistication defined by technology, either real or conceptual. Style, thus, becomes a ramification of a certain technological level, and a stable non-evolutionary technology would in effect produce a styleless art, if the results of such a marriage could still be termed art.

While it is reasonable to suppose that the constructions of Castro-Cid cease to represent the classical image of sculpture, it is equally relevant to question whether figures in bronze and marble still symbolize the form-creating ambition of our culture. It is obvious that they do not, and we are less and less inclined to pretend that they do. It has been retorted, though, that an art form so intensely technical as Cyborg Art cannot but lack in spiritual vigor. Still, we might answer with Spengler: what a culture shapes with its life blood—be it an ethical system, architecture, or a spaceship—represents the quintessence of its spiritual destiny. An artist such as Castro-Cid constructs mock cybernetic systems, not in hopes of producing another stylistic tremor, but because they represent the technical and spiritual will of our civilization.

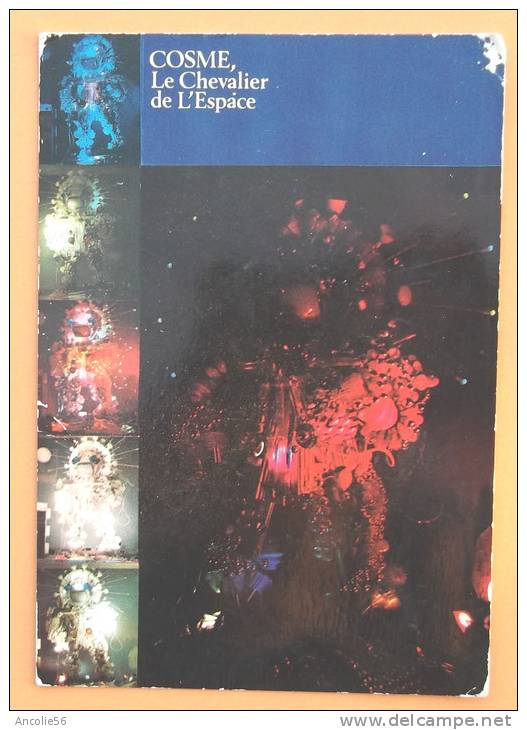

Enrique Castro-Cid , 1965.

Source: Cornell Daily Sun-1965

Enrique Castro-Cid Chilean Artist's Robots Show Machines Can be Playful

By DIANE P. WEINSTEIN

Two foot-tall robots on a large plexiglas platform playfully buffet and "elbow" each other about. A larger robot moves across the floor with a pumping red, rubber heart in his chest. A fourth, confined to a basin under a plexiglass dome shifts futilely back and forth. Another waves red tentacular arms in slow circles and blinks a solitary light bulb. Their creator is Enrique Castro-Cid, a young Chilean artist and art critic with long, thick black hair and a generous smile. Castro-Cid arrived at the University yesterday as a guest of the College of Architecture and will remain on campus until tomorrow, lecturing, observing classes and criticizing the artwork of Cornell students. Although his family encouraged a legal career, Castro-Cid was diverted from law school to the study of art and served as an assistant professor of drawing in Chilean University. The difficulties of making a living in Chile, where artists receive few subsidies and awards, led him to the United States four years ago. Castro-Cid has since had two successful one-man shows and was recently awarded a $5000 Guggenheim Fellowship. His unique creations glide, stalk, hover, float, flirt and even think. This past month a force of Castro-Cid's robots and automotons flashed their playful personalities and conquered New York City's Feigen Art Gallery. Children were fascinated, but their parents were more captivated by these plexiglass, wood, and plastic robots and rapidly bought out the show. Modern society, Castro-Cid feels, is unduly preoccupied with the "Faustian" evil of machines. Much of today's science ficton depicts a bleak future where unfeeling, dominant machines enslave their human creators. For many, automation portends mass unemployment and a society suffocated by the glut of leisure time. A cheerful advocate of the idyllic "Dionysian" society, Castro-Cid is most optimistic about the present trend. Contrary to traditional belief, he feels that labor is not the moral ideal. He makes the sympathetic observation that "to work is terrible if it is not thoroughly enjoyed" and hopes that automation will make the drudgery of labor obsolete. His machines are "playful" and personable and therefore very likeable. They were originally intended for Castro-Cid's own amusement, and their foremost purpose is to be enjoyed. The inventions, however, also illustrate some of the complexities of modern life. Two ping pong balls, red and black, fight for a single current inside a wire container. The head-shaped cage, Castro-Cid explains, represents the human mind where ideas compete for precedence in a randomly-directed stream of thought. An electric train buffets a black ping pong ball around a circular track. At one point the ball is trapped by an upward stream of air while the circum-navigating train tries to pass a loop around it. Statistically, Castro-Cid explains, the shakily hovering ball should pass through the hoop in two out of every 20 trips. Castro-Cid added he believes this paradox of the "limited or ordered random", freedom within a restricted area, reflects the condition of modern man. Accident and order are equally significant in human existence, he said. Castro-Cid explained he has attempted to demonstrate the complexities of the machines and the human mind by mimicking both in his anthropomorphic technology. He does not ally himself with "pop" artists who, he claims, establish their rather weak points by mis-placing everyday objects such as soup cans and brillo boxes. He was enthusiastic, however, about the work of Cornell student artists who he considers "on the par with professionals." Castro-Cid's first show, entitled "Ideas for Fantastic Zoology," dealth with compound anatomies, his preoccupation before robot art. Inspired by studies in the American Museum of Natural History, the artist concocted "jaberwocky" creatures whose organs and appendages logically fulfilled the animal's needs. Castro-Cid explained this inventiveness in painting to mechanical innovation. Working at home, frequently in energetic late-night sprints, he has produced 20 works in the past seven months.

Enrique Castro-Cid – Pioneer in Latin American Art

Published: August 17, 2011 – Source – here

Enrique Castro-Cid burst onto the art scene with ferver. He had arrived in the United States to a hungry New York City waiting for the next big thing. Awards, Guggenheim Fellowship Grants, exhibitions at galleries and museums followed briskly after his early 1960's arrival. He immediately became a darling of the art world. Dashing good looks and a Latin American style led him to marry first a Harper's Bazaar cover model, Sylvia, and then an art patron, Christophe de Menil. Enrique Castro-Cid formed and broke relationships. Forming and breaking are two sides of the same coin. The human form is as it looks, until of course you change the perspective, the coordinates plotted onto a graph in space, change your way of seeing. Welcome to a look inside the world of Enrique Castro-Cid.

He was born in Santiago, Chile in 1937. Art studies at the Escuela de Bellas Artes at the Universidad de Chile would commence some 20 years later. Shortly after his studies came to a close, he found his way to New York City. His loft was something artists dreamt about, huge and full of potential. That was Enrique Castro-Cid. He was a larger than life figure whose ideas about art could not be confined to a mere three dimensions. He wanted more. Four, five, six. Why did there have to be limits on the imagination?

He pioneered the relationship of computers, geometry and art. His vision was one of space-time. His limitless imagination and command of the computer in the 1960's and 1970's allowed him to create art that would be conceivable in the computer, but difficult to represent – five dimensional space being one of those ideas. He would come to be considered an avant-garde psychologist of perception. He experimented with pictorial space and with geometric transformations. He took his art and way of understanding to another level. Or two…

Castro-Cid drew our attention to many questions. How do we perceive a deformation? How do we perceive a face? Is a face a face whether it is smiling, frowning or impassive? How do we know that expression, if we have never seen the face before? His art explored these concepts. He would draw the human nude form and the outline of that form would be plotted carefully on a graph. As he changed the formula and the equations, the outline of the form would seem to distort. The equations were then changed to such a degree that the form, once known to us, now seemed almost unrecognizable. Or, were we looking at the process backwards? Were we looking into other dimensions?

But perhaps, he as an artist was only experimenting with these ideas and never meant to delve so deeply into such questions. But that is the nature of art. It beckons you close, then pulls you in. You are asked to understand something that may never be understandable.

Castro-Cid's time in New York City had come to a close, he headed for warmer climes and arrived in Miami in the 1980's. Of course, once again he was a celebrated figure on the art scene and was once again given many awards and exhibitions. He lived a fast paced life in Miami, a roller coaster ride for all those who dared to climb on board. He was a Latin American artist living the American dream. Following his desires, his dreams and his own path into space. He created art for a select few who cared enough to see his vision.

The technology of Computer Aided Design and such new programs as are used today, can see their ancestry in his art. Certainly a branch of the family tree. He was the root. He helped to create a movement that exists to this day. His work has long lived past him. He died of a heart attack in 1992. 54 years. A lifetime of ideas. A vision that will last the test of space-time.

Mechanical Hound – "Fahrenheit 451"

It has been claimed elsewhere that Castro-Cid constructed the hound for the movie "Fahrenheit 451" . If he did, it was never used.

Fahrenheit 451 (first screened 1966)

The Making of Fahrenheit 451 (as per DVD bonus) – Reference to "The Mechanical Hound"

Ray Bradbury: One of the flaws of the film, for me, is the absence of the Mechanical Hound, because he's a feature that helps tell you about the future.

Producer Jay Presson Allen: I thought the robotic dogs and so on would be very, very difficult and really not what he [RB] was trying to do and , I mean, it would be very distracting, in fact, from the simple story of the books, which is really what he was interested in most of all so I think he was quite proper to avoid, the more or less conventional science fiction. there were so many coming out at that point, and I think they made the right decision to withdraw from that and not make that the overwhelming aspect of the film.

**Update Feb 2016: I've been contacted by Dr. Barry Ragone who has the original drawing of Castro-Cid's Mechanical Hound (dated 1965). He has asked me not to publish it, and also requested a critique, which I've reproduced below:

Hi Barry,

Thanks very much in showing me the drawing. By not being numbered, it is a one-off, and its intended use to be the plan to build the actual dog from, and not as an art print! Very unique.

My initial thoughts were that you had not sent me pictures of a 'hound', but of a beetle. The legend in the drawing obviously says otherwise.

Based on that initial surprise, I've tried to be critical in context of the era i.e. 1965, the technology available, the artist's style, and the possible brief from the director / props team.

The hound in the book is eight-legged and injects one with a hypodermic needle from its mouth.

The real-life fire-station dog tended to be more a mascot than a working dog, hence the Dalmation. Hounds are sniffer dogs, or more sinister as in Conan Doyle's "The Hound of the Baskervilles".

To my knowledge, there were no robotic dogs in movies prior to 1965. The first I can come up with is "Snooper" from "A View to Kill" – James Bond 1970; Rags in "Sleeper" in 1973, then "K-9" from Dr Who, 1977. However, "Cyber", a cybernetic dog was built by Bruinsma in 1958 – 4 moving legs, and dog-like.

Some critics of the 1966 movie say that it wasn't as good for leaving out the 'mechanical hound'. Even if the actual robot could not perform as expected, certainly the use of special effects would have been sufficient, in my opinion.

Thanks again for sharing with me.

See other early Robots in Art here.