Object as Index: Ernesto Oroza in conversation with Gean Moreno

In Florian Borchmeyer and Matthias Hentschler’s lop-sided film Havana: The New Art of Making Ruins, 2006, Cuban writer António José Ponte, one of the protagonists, fires up his brain’s associative engine. Eruditely crossfading from Thomas Mann to Georg Simmel to Jean Cocteau, Ponte reveals himself a modem initiate in the ancient discipline of ruinology- like Walter Benjamin and Robert Smithson. One of the most interesting proposals he puts forth-interesting at least for those of us who know fantasy’s edges always cut across the real—is that Havana, the dilapidated Havana of today, is the result of the coming imperialist invasion on which the regime’s rhetoric has pivoted for decades. Waiting for this invasion, the city transformed itself into besieged territory. Haunted by its future destruction, the city destroyed itself.

Ernesto Oroza’s work seems to unfold against this kind of sweeping and romantic narrative. Instead of re-editing the establishing shots of a dilapidated Havana that have now become icons around the globe, 0roza is interested in the other Havana- the place that can be discerned in the quotidian textures of popular design and improvisational ingenuity, in the everyday transactions that take place in order to satisfy immediate needs. This Havana exists in the activities of its inhabitants, and functions almost as a foil to the other Havana, which we can no longer disassociate from grand historical trajectories.

Coming of age with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet subsidies that kept the island economically afloat, Oroza belongs to a generation of artists who emerged with the Special Period—Cuba’s deepest economic crisis. Unlike many of his peers, however, he wasn’t brought up through the island’s centralized system of art academies. Instead, he was educated as an industrial designer. Oroza eventually found in the artworld an accommodating context, after he shifted his interest from actually producing and designing artifacts to documenting the realities of the island as they manifest themselves in the objects created by lay folk attempting to better their lives.

Oroza’s background becomes important when one begins to consider the oddity of his project, in comparison to those of his peers in the Cuban artworld. Unlike them, he has never found a need to produce autonomous objects, self-contained sculptures or photographs. On occasion, he has said that he doesn’t really know how to put his resume together, considering that what would go in it—exhibitions—is but a small part of what he does, an offshoot of a project that has more to do with collecting and organizing information. He has always approached things with a documentarian’s eye. This is evident in the research projects that he has conducted, in the books that he has published, and in the photographic archives and collections of objects bought in the street that he has amassed. But it is also true of the individual, sculpture-like objects and videos that he often presents in exhibitions. They reproduce the logic of popular design enacted in every household in Cuba in the 199os, taking on an indexical quality, pointing to real socioeconomic conditions. In some ways, he is like the European conceptualists of the 1960s, who sought to develop materialist practices by representing what the world had to offer in order to articulate critical positions on the way things were. In this, a seemingly distant figure like Marcel Broodthaers may be more of a predecessor for Oroza—taking into account obvious contextual differences— than installation artists such as Lázaro Saavedra, Ricardo Brey, José Bédia, and Tonel, who launched a tradition which his peers are carrying on.

Gean Moreno: There is a discourse that revolves around Havana as a ruin, as what is left after certain historical processes have run their course. Your work refuses to contribute to this discourse and, instead, proposes that such a reading is applied from the outside, and that the city has its own internal history.

Ernesto Oroza: There are really two discourses that connect around the idea of the ruin while they stand ideologically opposed to one another. The first considers it necessary to return the city to its original functional and symbolic values. On one hand, it seems a criticism of the existing political system, whose inefficiency brought about the destruction of Havana. On the other, it is aligned with official interests insofar as it hands the city over to tourism, and reaps the benefits on the way. This is the position of architects and conservators.

The second notion of the city as a ruin comes from the outside. People see the city as kidnapped. Very little has been built, officially, in fifty years. As a result, the city represents the political system that was deposed in 1959. But this perception—of the city as a ruin—empties Havana of its inhabitants; it negates the efforts of families to make habitable a city whose population has grown without any official rise in housing capacity.

As such, in addition to an internal history, there is also a city that has grown inwardly. Families have found solutions to meet their needs. These adaptations have turned Havana into a continuum of internal transformations. The phenomenon is so widespread that we can speak of a familial urbanism, set in motion from every Cuban household. That is the city that interests me and that produces my work.

GM: This widespread phenomenon exists, then, at a quotidian level. Your interest lies in popular design that aims at the immediate betterment of living, responding to real-time needs, without historical pretence or institutional legitimization.

E0: Exactly. Let me explain the context. As I was finishing my studies in industrial design, Cuba entered the most profound economic crisis in its history, due to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Cubans understood that they would have to meet their own needs, as they lived in a country where the State owned all productive capabilities. Urgency placed the individual at the center of the country’s survival. People became aware of their real needs and were freed of prejudices and banalities.

Necessity has been stigmatized in Western culture. If you find yourself in need, you are considered weak. If you make demands to meet these needs, you are considered vulgar. Since the 1990s, Cubans have done violence to this stigma. Each object produced or solution discovered has been a statement of principle. I’ve called this state of awareness and freedom Statement of Necessity and what it produces Objects of Necessity.

As a cultural producer, I wasn’t spared those penurious conditions and I felt a part of the productive current that they engendered. I began to document the ideas and techniques that I saw everywhere. The objects produced at the time expressed provisionality, a utopian pragmatism that is quite paradoxical. We all thought that the crisis would end quickly and we decided to make provisional objects. These would substitute the ones that belonged to a time with a higher standard of living. They were objects that would disappear with the conditions that engendered them. I found it important to document them. These objects embody an ethics and a modesty that are the opposite of the ostentatious presumptions of innovation and transcendence that are pushed on us in design school.

GM: You said that you found it important to document the objects that were emerging in light of the conditions brought about by the economic crisis. This reminds me of a concept that you’ve used before: the object-documentary. An object that, like a film documentary, records an existing reality instead of inventing a new one—as traditional art objects presumably do.

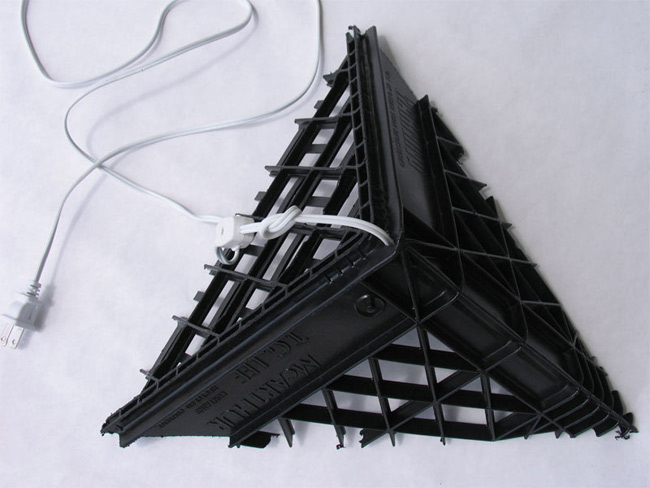

E0: I became aware of the processes I was using. They became more interesting than any theme. All my recent production has followed one of two processes. The decorative documentary would be the first. I figured out that the placement of a series of collected objects in an art space complicates their documentary function without losing the value of the document altogether. I was attracted by the ambiguity between display and sculpture. A typical work, here, would be Untitled. Decorative Documentary, 2005, made of metal strainers. On the one hand, it is just a cold presentation of collected objects. On the other, it materializes an abstract sculpture that establishes a relationship with the space that houses it.

My interest in simulating materials like Stone and wood can also be seen to belong to this process. In this type of intervention, however, the space of the simulation—its support—is crucial. For instance, when I selected the visitors’ bathroom at the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba, and covered it with a simulation of wood—for which an expert was hired—I introduced vernacular taste and know-how into a legitimate art space. I also managed to make people disclose their repulsion for popular practices, with their inevitable reading of the bathroom as covered with excrement.

At the Ludwig, I also placed a collection of decorative objects that I purchased throughout the city. They functioned simultaneously as documents of a popular aesthetic production and as decor.

My other process is the multiple documentary: the placement of two or more documents on a single support. Disparate associations are established among the documents, allowing the information to be interpreted in unforeseen ways. Most difficult in this case is the choice of material to be documented, as I don’t want to start with a preconceived notion of how things will end up. For this reason, I turn one of the documents into the support by emphasizing some of its formal, physical, and conceptual traits. For my next project of this type, I want to juxtapose some staples of Cubans’ diet with the water and electricity conduit systems that they use to transform their houses. The tubes will be filled with the food.

GM: Your de-emphasis of the autonomous art object has allowed you to maintain an open practice. Along with objects and installations for exhibition, your work also consists of a series of researches that find their final forms in books, zines, lectures, photographic archives, and collections of objects. As such, your work is more a discursive field than a group of things.

E0: I work with disparate materials and information that I organize into diverse conceptual frameworks, such as books, displays, and even my own drawers. I’m more interested in developing systems to articulate the information that I process than in producing “definitive” works. I neither desire nor need to produce objects with the expected attributes of autonomy, authorship, originality, unity or physical limits, that is, the qualities intrinsic to the traditional artwork.

In fact, when my work is presented in traditional exhibition spaces, I appropriate interventionist logics from other disciplines, such as interior design and architecture. On occasion, I also use models and principles of production from the fields that I study, and extrapolate on them for my own practice. I am a pragmatist. Just as someone uses a telephone as a base for a rehabilitated fan, I use diagrams that others have created to illustrate phenomena foreign to my field in order to explain my ideas.

Such transaction allows the ethics, the phenomena, and the essence of the foreign field to seep into my work—this very stimulating. I don’t feel the need to define the limits or the Reading of my work. Only when it is at risk of being consumed does it assume a precise shape, but only to dissolve afterwards. It’s as if every one of its components always returned to its source.

2008. Moreno, Gean. “Object as Index: Ernesto Oroza in conversation with Gean Moreno” Art Papers, May/June p.24.