Curated by Nicholas Frank

University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee Peck School of the Arts

Curator’s Statement

Download Tabloid printed for the exhibition

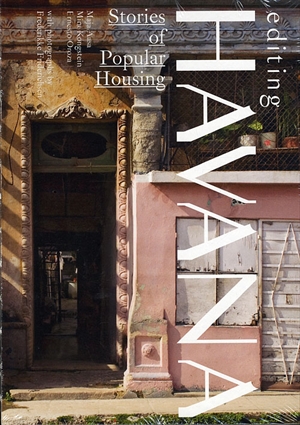

Ernesto Oroza’s “Architecture of Necessity” chronicles the inventive solutions that arise under conditions of severe economic limitations, such as those in his native Havana. The island nation of Cuba has been embargoed and isolated for decades and restricted by an authoritarian government, and deprivation is the norm. Though private production is illegal under the current system, people invent the things they need, and make changes to their built environment as necessary.

Oroza’s work (in essays, photographs, collected and reconstructed objects) documents the range of inventive solutions borne out of these conditions, while charting a moral course for social discourse and development.

The exhibition at Inova will feature a combination of interior design and architectural elements, along with documentary photographs of architectural modifications in Havana, and video detailing various household inventions. Inova will publish an edition of Oroza’s Tabloids, an ongoing project that conveys ideas and visual information in an inexpensive and widely distributable format. The Inova tabloid will act as the exhibition publication for the concurrent shows (Matthew Girson and Jeanne Dunning), and contain information specific to the Milwaukee community. We are grateful for the support of the Walker’s Point Center for the Arts and Aprenda Invertir (Miami).

This is Oroza’s first exhibition in the Midwest.

“The need for raw materials converts these places into very selective “black hollows”. All the plastic objects from the surroundings were absorbed by the mechanism, a kind of industrial cannibalism. Hordes of plastic prospectors were collecting containers from everywhere to feed the monster that was expelling little heads of Batman at the other side. Sometimes families were living with the machines inside the house, not in a patio or a cellar. A room during the day can transform itself into a plant to produce electric switches, pipes or hoses. Photos of children on the wall of the house and a small bedside table now used as a toolbox reappraised the past of the space.”

From: Menu, Baptiste. Réactions en chaine Interview with Ernesto Oroza. Azimuts 35, Cite du design, 2010.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video (100 slides), two mobile projections, random music

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video (100 slides), two mobile projections, random music

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video (100 slides), two mobile projections, random music

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video (100 slides), two mobile projections, random music

-

-

Architecture of Necessity

General view

-

-

Architecture of Necessity

General view

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011

Video installation, details. Marble plastic surface from plastic cups, jewels, toys made by families at home, using reinvented injection machines. Row material: scavenged plastic around the city: discarded auto pieces, stolen trash urban cans, plastic bottles.

-

-

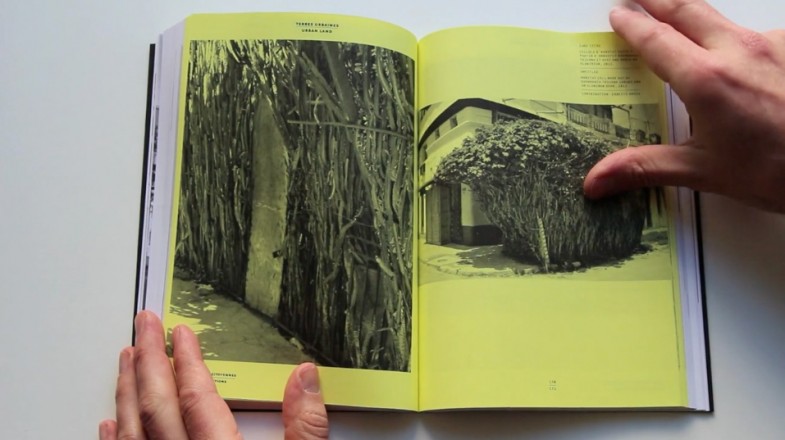

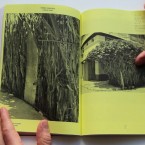

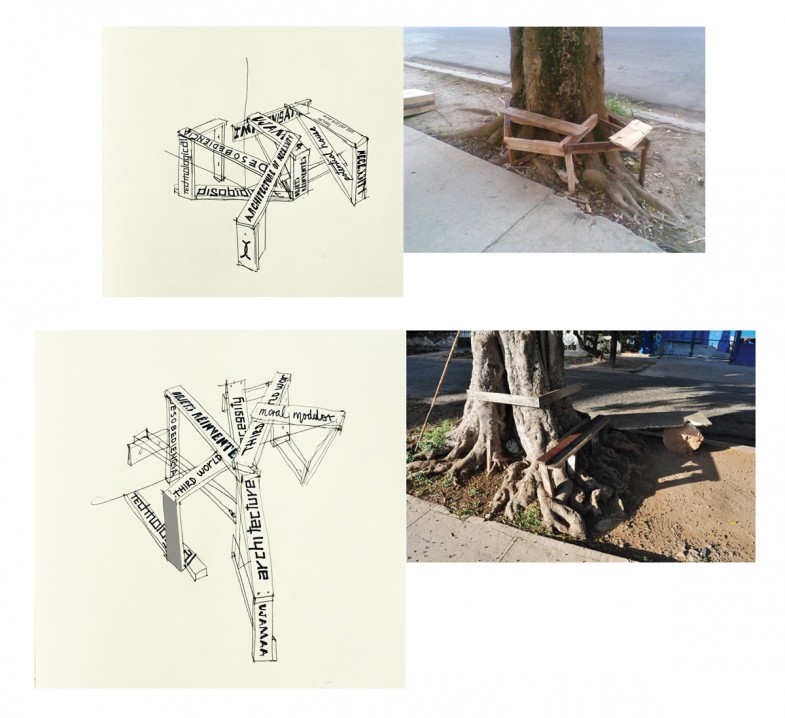

Moral Modulor 1997-2008

-

-

Moral Modulor 1997-2008

-

-

Architecture of Necessity

General view

-

-

Ernesto’s portrait swimming with plastic bottles

newspaper,cut

-

-

Fence

newspaper, cut

-

-

Moral Modulor’s Drawings Project “When anthropometric dimensions become a metaphor for moral dimensions”,

newspaper, cut

-

-

Moral Modulor’s Drawings Project “When anthropometric dimensions become a metaphor for moral dimensions”

Collage,

-

-

Architecture of Necessity

General view

-

-

Architecture of Necessity

General view

-

-

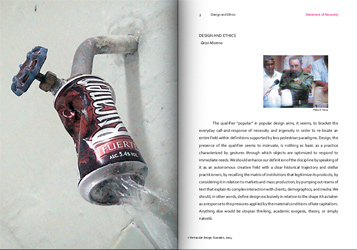

Technological Disobedience, Little Havana Lamp shade, 2009

Clear silicone

-

-

Technological Disobedience, Little Haiti Lamp shade, 2007

Scotch tape

-

-

Tabloid (special edition), 2011; Paperweights, 2007

newspapers, cast cement

-

-

Booklet “Disobedience”, 2010; Paperweights, 2007

newspapers, cast cement

-

-

Tabloid installation (special edition), 2011. General view.

-

-

Tabloid installation (special edition), 2011. Pattern documented by Ernesto Oroza (Havana, 1997-present)

-

-

Tabloid installation (special edition), 2011. Pattern documented by Ernesto Oroza (Havana, 1997-present)

-

-

Tabloid installation (special edition), 2011. Pattern documented by Ernesto Oroza (Havana, 1997-present)

-

-

Video proposal “Redrawing INOVA”, 2011

Video, color

RÉACTIONS EN CHAÎNE

Interview with Ernesto Oroza

By Baptiste Menu

(The english version of this interview was published in the special tabloid printed for the exhibition Ernesto Oroza. Architecture of Necesitty, INOVA, 2011) (French version)

Baptiste Menu What you call “technological disobedience” is questioning the life cycle of western products, by multiplying the industrial objects’ length of use up to the limit of their possibilities of use. This system is now possible thanks to the reconsideration of the industrial object under the hand-craft aspect.

Which forms of organization does this creative re-conquest of industrial objects take?

Ernesto Oroza I think the fact of reconsidering the industrial product from a hand-craft perspective encourages shrewd practices in contrast with the artificial voracity and activates more human temporary relations, like the repair, can authorize questions about the obtuse nature of the contemporaneous industrial object. When you open an object to fix it, there is a crack in the authority system which is set up. We see the internal organs of an authoritarian logic that imposes itself not only through a product but also through a system sequence : the objects integrate authoritarian families, share an infinite succession of reinforced generations. And this domination even precedes the arrival of the object at home; indeed its first domination takes place in the mass media. That’s why I used, in the ‹Rikimbili. Une étude sur la désobéissance technologique en quelques formes de réinvention› book, the image of Fidel Castro on the national television selling to Cubans a Chinese product used to boil water. The image couldn’t be much redundant and excessive in terms of imposition. When I talk about authority, I want to link it with all the logics these products induct, starting with the imposition of their scheduled life cycle.

Concerning your question about the forms of organization that qualify and diversify the hand-craft revision of the industrial in Cuba, I would comment one of them, which is fundamental to me: the accumulation. It seems to be a passive act, not creative, but it is literally the organizational starting point of the phenomenon. I grew up in a family where we kept everything and everything seems to have a potential. Each object accumulated by my mother can perfectly be useful in a situation of future shortage. The accumulation is in fact an emergency exit from an inopportune crisis, but it becomes a habit, because of distrust. The accumulation is regularly the first gesture in the production process and it has an absolute manual nature. That is to say that from the accumulation yet, you begin from a hand-craft point of view to be disrespectful to the life cycle integrated in the western industrial object. You infinitely postpone the moment of its waste by separating it from its assigned route. I think that the fact of accumulating things inserts an alteration, a notion of time, in the Cuban vernacular practices and this new own time organize them, give them the form of a parallel and productive phenomenon. I also said that the fact of accumulating is not only the suspicious fact of piling up objects. Well, when you do that you accumulate ideas of use, constructive solutions, technical systems and archetypes in general that can flourish when the situation gets worse.

Illustrations from: Con nuestros propios esfuerzos. Editorial Verde Olivo, 1992

BM I have the sensation that an important concept runs through your work, the material-object notion. Can you develop this idea, please?

EO I’ ve been writing recently on the issue related the re-use of generic objects as buckets or milk crates in precarious contexts like in Little Haiti, in Miami. Even if the situations are different, Cuba is characterized by a profound shortage and the US by an excess of products. In each case, there are social groups living in bad conditions. I met in each territory similar patterns of behaviour. It seems that people in these circumstances generally perceive their material universe in a discriminative way. They are just interested in the physical qualities of the objects that surround them. It’ s a diary process, an appropriate activity. When we look at the object from the exterior, we can understand it as the potential and real re-conversion in raw material of all the elements that integrate the environment of the individual. This process begins by erasing the objects’ and parts’ meanings present in our culture. That is to say that an individual recognizes in a bucket a kind of cultural profundity. But, when he is in a situation of need, he will just perceive it like an abstract compilation of materials with forms, edges, weight, structures. We can make a very familiar parallel with the relation of use we have with the natural world. It is normal to take a stone to hold a door or a branch to reach a fruit. The rhetorical or historical value of the stone won’ t be important when you need to let the door open, only its weight. A bucket full of water can only be used to block a door. The relation we maintain with things in both universes (natural and generic) comes from a unique condition: the two objects, the branch and the milk crate, suffer from identity. They seem to be foreign to the system of sense production, foreign to the culture. A plastic box to distribute milk is an abstract and autistic object, dumped through a circle of very specific requirements and that’ s why an object is accessible thanks to its excessive production. I wonder if the description fits with the branch or the stones’ one. For sure, the box has a social function, but its conception has been so much optimized that the human aspect has just become a value, a dimensional data within the plastic surface of the object, as it is for the weight of a litre of milk or the storage capacity of the truck that supplies it. The milk crate is a field sown with physical qualities, potentialities that will become more visible as far as we will have more needs, and it is also a field empty of sense. Its figure is so quiet in terms of image that its indifference and the indifference of the system producing it overwhelm us. Everyday the box travels full and comes back empty. It takes parts in a loop that could remain active for the eternity. If a box goes out the loop, lost or damaged, another one will replace it. If the world suddenly halts, the circle made by the boxes of milk in the city would continue to flow. We would be frightened by its social indifference, its pensiveness, the silence its centripetal move produces. But, around this circle or in a tangential scheme, there are circles of human activities eroding the perfection of the rational system where the milk crate subsists, splintering. The surrounding zones of the markets where milk is distributed are full of milk crates used like urban seats or used for other activities like car washing or water selling. In order to explain you how this occurs in Havana, we can use the example of the fan repaired thanks to a telephone. A quick glance to the object will carry us away from the art field of senses, from the readymade and from the index of associative resources of the Dada where the humour articulated with the image takes our look and our understandings. Nevertheless, for the repairman, the telephone is the unique form, similar to the original prismatic base, he could access to. When the telephone broke, he didn’ t throw it, the necessity made him suspicious. This telephone had been made in the ex-German Democratic Republic as it seems it stayed ten years under the bed or in a wardrobe. When the body of the fan broke, perhaps because of a fall, the family should be worried. A temperature of forty five degrees centigrade is a very difficult situation, the impossibility of replacing the object, because of the excessive disparity of wage, closes the debate. He has to assume the repair ; the accumulation he continued for years has a parallel existence in his memory. He remembers the old telephone. He only takes into account the physical attributes of the object. The angles and the internal plastic nerves that shape this prism with rectangular base assure the stability of the fan. The symbolic association that could appear after the repair are invisible for him. The pragmatism makes the reconstructed body of the object avoid any kind of symbolic construction intent. In Cuba, the process looks more severe as it begins with the flattening of the object’ s identity. In the US, the generic object seems to hide its identity, it yet comes flattened. From this, for the people of the Havana and from Little Haiti, a new field to pick physical virtues is open. Finally, I recently begin to associate this phenomenon to the ideas of Oswald de Andrade, specifically to his Cannibalistic Manifest (one thousand, nine hundred twenty eight). Helio Oiticica uses it to elaborate the “Super-cannibalism” concept considering an “immediate reduction of all the influences exterior to the national model”. By focusing the process on the productive universe and on the Cuban material culture, I can’t stop seeing it, literally like a super chewing, a super riding. It’s a violent action, in cultural terms, against the colonial material universe that surrounds us and which seems to be unable to solve the people life. But it is, over all, a foundation gesture to implement practices of disobedience from which it is impossible to evacuate ideological components around a culture of resistance.

Illustrations from: Con nuestros propios esfuerzos. Editorial Verde Olivo, 1992

BM In this context, you study the way Cubans have been able to re-appropriate the means of production and to develop what you call “the vernacular industrial production”. What is this?

EO I consider it like an appropriation of the productive management, but not of the productive system. The State means have been idle for a long time. The industry paralyzed. There was no raw material and the government had lost its markets.

The Cubans created a parallel productive space, constructed machines in their houses, workshops, tools. In some cases, they parasitized the State industry where they were working; creating productions on the sly, with illegal timetables, but it is not the most usual method. The lamp of extracted acrylic we showed in the book ‹Objets réinventés› connects the two variants: the appropriation of State productive means and the creation of parallel means of production.

It was discovered by some workers during a power cut in the nineties. When the blackout occurred, the Japanese machine used to produce rods for artificial insemination remained full of acrylic in its pipes of extrusion. So, it was necessary to drain it manually and in emergency. The acrylic expelled drew in the room elliptic lines and came tough, forming a complete figure and decorated by the gravity. With their gloves put on, they began to model in the air and to experiment forms that resulted ashtrays, centrepieces… I think that the workers had been waiting with joy and for a long time the forthcoming power cut. They had a legal protection to produce: they just had to save the machine from an obstruction and this liberation allowed they to produce something they could conserve, the expelled material was considered as a waste. One of them thought he could create such a machine at home; the device used to produce fritters was an analogous model. Since then, they did not need the State productive space anymore. They did not need either the Japanese machine that was ordered a power cut each three days. The access to the acrylic was the most complicated thing, but a black market appeared for this product. There were warehouses with immobile raw materials. The State had remained paralyzed, shocked by the crisis impact and he didn’ t react. The individuals found very quickly the responsibility in them for the productive management. The implementation of a familial industry in the ninety’ s, still active, is bound to the production of plastic and aluminium objects. The scale of the productions was so big and visible that they needed a patronage, a legal source of income and support. It is not the same thing to sell illegally ten lamps of kerosene made with beer tins and to sell three thousand plastic glasses. Indeed what was called “the local industries” came on stage. It was a State institution that gave job opportunities to some craftsmen and workers. It was unifying small workshops spread all over the city a long time before the revolution: printers of Linotype, workshops of sewing, of cobblers, workshops to produce craftworks. When the crisis appeared, the local industry was the unique skilled model the State had to regulate the vernacular productive torrent. It was used as a mediator to access to the raw materials, to distribute goods and later as a controller of the tax paying, to keep an eye on the illegal practices and appropriate the inventiveness and the popular effort.

The workshops in houses turned into living systems in the centre of the city. They employed young people of the area. Sometimes you could see them enter stealthily behind a tree: it was the thin access to an improvised cellar where there were two or three machines of plastic injection. The mechanisms were incredible, they produced them by themselves. Also the moulds. The need for raw materials converts these places into very selective “black hollows”. All the plastic objects from the surroundings were absorbed by the mechanism, a kind of industrial cannibalism. Hordes of plastic prospectors were collecting containers from everywhere to feed the monster that was expelling little heads of Batman at the other side. Sometimes families were living with the machines inside the house, not in a patio or a cellar. A room during the day can transform itself into a plant to produce electric switches, pipes or hoses. Photos of children on the wall of the house and a small bedside table now used as a toolbox reappraised the past of the space. I can’ t stop using these examples to answer you. In the order of the definitions, I think that the words “domestic or familial industrial production”, allow determine a more complete form of production that holds an implicit increase of the series characteristic and of the volume of production, but that remains especially associated to the house and that mixes its activities with the domestic tasks of the family. Other vernacular and familiar features in these productions, responding to appropriation gestures, can be found in the elaboration of the designs and in the inspiration sources. In a certain way, the objects present in the house before the crisis supplied a guide to get some values by appropriating the form of a glass. They used its dimensions, decorations, ergonomic values. The family recycled the formal universe coming from the exchanges of Cuba with the communist Europe. It had a second life embodied in the multicolour plastic or aluminium.

Illustrations from: Con nuestros propios esfuerzos. Editorial Verde Olivo, 1992

BM In front of a perpetual emergency, these practices of reinvention extend themselves to all fields of the everyday life. You say that “the city takes place at the biological rhythm of the house”, a strong image you employ is the potential house. Would you please tell us more about this thin link between the Human and its constructed environment?

EO The crisis persistence and the hope loss in the socialist government productivity generated a mentality, a social being that I called, revisiting Le Corbusier: the Moral Modulor. I talk about an individual or a family pushed in some circumstances under the poverty line (below zero would say Glauber Rocha).They can proceed to a moral reinvention. Their actions will occur in a threshold or a moral frequency where you can’t see old historical and esthetical values, social status, urban standards and codes of citizen behavior in general. That is to say, all these conventions relative to an order now hostile and restrictive of the family survival will be questioned. The individual will register this freedom in his spaces and objects, next to the order of his foot; he will set up an unknown moral dimension. The house, and the city by extension, becomes a continuous diagram of the shrewd relations of the individual with his needs, the contextual limits and the available resources. I told in other occasions that the facades are like films displayed from the middle of the house to the exterior. They talk about the past and the recent life of the family. Indeed, they announce plans, threaten of invasions or inform on future metamorphosis and fusions: staircases which don’ t fit to any side, walls that figure expanding to all interstices, baths open to the public sight, terrace roofs invaded by materials and heterogeneous accumulations. The house like a finished entity doesn’t exist anymore. The house is like an organism that auto-constructs itself in time to the human rhythms living in it. What I call Potential House, or more recently Convergent House, is a way to live in the process (of living). I think there is no better diagram to explain the relations you ask me than the houses themselves, their surfaces, spaces and structures.

Stills from Untitled (cabaret a la deriva), 2011