Object as Index: Ernesto Oroza in conversation with Gean Moreno

In Florian Borchmeyer and Matthias Hentschler’s lop-sided film Havana: The New Art of Making Ruins, 2006, Cuban writer António José Ponte, one of the protagonists, fires up his brain’s associative engine. Eruditely crossfading from Thomas Mann to Georg Simmel to Jean Cocteau, Ponte reveals himself a modem initiate in the ancient discipline of ruinology- like Walter Benjamin and Robert Smithson. One of the most interesting proposals he puts forth-interesting at least for those of us who know fantasy’s edges always cut across the real—is that Havana, the dilapidated Havana of today, is the result of the coming imperialist invasion on which the regime’s rhetoric has pivoted for decades. Waiting for this invasion, the city transformed itself into besieged territory. Haunted by its future destruction, the city destroyed itself.

Ernesto Oroza’s work seems to unfold against this kind of sweeping and romantic narrative. Instead of re-editing the establishing shots of a dilapidated Havana that have now become icons around the globe, 0roza is interested in the other Havana- the place that can be discerned in the quotidian textures of popular design and improvisational ingenuity, in the everyday transactions that take place in order to satisfy immediate needs. This Havana exists in the activities of its inhabitants, and functions almost as a foil to the other Havana, which we can no longer disassociate from grand historical trajectories.

Coming of age with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet subsidies that kept the island economically afloat, Oroza belongs to a generation of artists who emerged with the Special Period—Cuba’s deepest economic crisis. Unlike many of his peers, however, he wasn’t brought up through the island’s centralized system of art academies. Instead, he was educated as an industrial designer. Oroza eventually found in the artworld an accommodating context, after he shifted his interest from actually producing and designing artifacts to documenting the realities of the island as they manifest themselves in the objects created by lay folk attempting to better their lives.

Oroza’s background becomes important when one begins to consider the oddity of his project, in comparison to those of his peers in the Cuban artworld. Unlike them, he has never found a need to produce autonomous objects, self-contained sculptures or photographs. On occasion, he has said that he doesn’t really know how to put his resume together, considering that what would go in it—exhibitions—is but a small part of what he does, an offshoot of a project that has more to do with collecting and organizing information. He has always approached things with a documentarian’s eye. This is evident in the research projects that he has conducted, in the books that he has published, and in the photographic archives and collections of objects bought in the street that he has amassed. But it is also true of the individual, sculpture-like objects and videos that he often presents in exhibitions. They reproduce the logic of popular design enacted in every household in Cuba in the 199os, taking on an indexical quality, pointing to real socioeconomic conditions. In some ways, he is like the European conceptualists of the 1960s, who sought to develop materialist practices by representing what the world had to offer in order to articulate critical positions on the way things were. In this, a seemingly distant figure like Marcel Broodthaers may be more of a predecessor for Oroza—taking into account obvious contextual differences— than installation artists such as Lázaro Saavedra, Ricardo Brey, José Bédia, and Tonel, who launched a tradition which his peers are carrying on.

Gean Moreno: There is a discourse that revolves around Havana as a ruin, as what is left after certain historical processes have run their course. Your work refuses to contribute to this discourse and, instead, proposes that such a reading is applied from the outside, and that the city has its own internal history.

Ernesto Oroza: There are really two discourses that connect around the idea of the ruin while they stand ideologically opposed to one another. The first considers it necessary to return the city to its original functional and symbolic values. On one hand, it seems a criticism of the existing political system, whose inefficiency brought about the destruction of Havana. On the other, it is aligned with official interests insofar as it hands the city over to tourism, and reaps the benefits on the way. This is the position of architects and conservators.

The second notion of the city as a ruin comes from the outside. People see the city as kidnapped. Very little has been built, officially, in fifty years. As a result, the city represents the political system that was deposed in 1959. But this perception—of the city as a ruin—empties Havana of its inhabitants; it negates the efforts of families to make habitable a city whose population has grown without any official rise in housing capacity.

As such, in addition to an internal history, there is also a city that has grown inwardly. Families have found solutions to meet their needs. These adaptations have turned Havana into a continuum of internal transformations. The phenomenon is so widespread that we can speak of a familial urbanism, set in motion from every Cuban household. That is the city that interests me and that produces my work.

GM: This widespread phenomenon exists, then, at a quotidian level. Your interest lies in popular design that aims at the immediate betterment of living, responding to real-time needs, without historical pretence or institutional legitimization.

E0: Exactly. Let me explain the context. As I was finishing my studies in industrial design, Cuba entered the most profound economic crisis in its history, due to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Cubans understood that they would have to meet their own needs, as they lived in a country where the State owned all productive capabilities. Urgency placed the individual at the center of the country’s survival. People became aware of their real needs and were freed of prejudices and banalities.

Necessity has been stigmatized in Western culture. If you find yourself in need, you are considered weak. If you make demands to meet these needs, you are considered vulgar. Since the 1990s, Cubans have done violence to this stigma. Each object produced or solution discovered has been a statement of principle. I’ve called this state of awareness and freedom Statement of Necessity and what it produces Objects of Necessity.

As a cultural producer, I wasn’t spared those penurious conditions and I felt a part of the productive current that they engendered. I began to document the ideas and techniques that I saw everywhere. The objects produced at the time expressed provisionality, a utopian pragmatism that is quite paradoxical. We all thought that the crisis would end quickly and we decided to make provisional objects. These would substitute the ones that belonged to a time with a higher standard of living. They were objects that would disappear with the conditions that engendered them. I found it important to document them. These objects embody an ethics and a modesty that are the opposite of the ostentatious presumptions of innovation and transcendence that are pushed on us in design school.

GM: You said that you found it important to document the objects that were emerging in light of the conditions brought about by the economic crisis. This reminds me of a concept that you’ve used before: the object-documentary. An object that, like a film documentary, records an existing reality instead of inventing a new one—as traditional art objects presumably do.

E0: I became aware of the processes I was using. They became more interesting than any theme. All my recent production has followed one of two processes. The decorative documentary would be the first. I figured out that the placement of a series of collected objects in an art space complicates their documentary function without losing the value of the document altogether. I was attracted by the ambiguity between display and sculpture. A typical work, here, would be Untitled. Decorative Documentary, 2005, made of metal strainers. On the one hand, it is just a cold presentation of collected objects. On the other, it materializes an abstract sculpture that establishes a relationship with the space that houses it.

My interest in simulating materials like Stone and wood can also be seen to belong to this process. In this type of intervention, however, the space of the simulation—its support—is crucial. For instance, when I selected the visitors’ bathroom at the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba, and covered it with a simulation of wood—for which an expert was hired—I introduced vernacular taste and know-how into a legitimate art space. I also managed to make people disclose their repulsion for popular practices, with their inevitable reading of the bathroom as covered with excrement.

At the Ludwig, I also placed a collection of decorative objects that I purchased throughout the city. They functioned simultaneously as documents of a popular aesthetic production and as decor.

My other process is the multiple documentary: the placement of two or more documents on a single support. Disparate associations are established among the documents, allowing the information to be interpreted in unforeseen ways. Most difficult in this case is the choice of material to be documented, as I don’t want to start with a preconceived notion of how things will end up. For this reason, I turn one of the documents into the support by emphasizing some of its formal, physical, and conceptual traits. For my next project of this type, I want to juxtapose some staples of Cubans’ diet with the water and electricity conduit systems that they use to transform their houses. The tubes will be filled with the food.

GM: Your de-emphasis of the autonomous art object has allowed you to maintain an open practice. Along with objects and installations for exhibition, your work also consists of a series of researches that find their final forms in books, zines, lectures, photographic archives, and collections of objects. As such, your work is more a discursive field than a group of things.

E0: I work with disparate materials and information that I organize into diverse conceptual frameworks, such as books, displays, and even my own drawers. I’m more interested in developing systems to articulate the information that I process than in producing “definitive” works. I neither desire nor need to produce objects with the expected attributes of autonomy, authorship, originality, unity or physical limits, that is, the qualities intrinsic to the traditional artwork.

In fact, when my work is presented in traditional exhibition spaces, I appropriate interventionist logics from other disciplines, such as interior design and architecture. On occasion, I also use models and principles of production from the fields that I study, and extrapolate on them for my own practice. I am a pragmatist. Just as someone uses a telephone as a base for a rehabilitated fan, I use diagrams that others have created to illustrate phenomena foreign to my field in order to explain my ideas.

Such transaction allows the ethics, the phenomena, and the essence of the foreign field to seep into my work—this very stimulating. I don’t feel the need to define the limits or the Reading of my work. Only when it is at risk of being consumed does it assume a precise shape, but only to dissolve afterwards. It’s as if every one of its components always returned to its source.

2008. Moreno, Gean. “Object as Index: Ernesto Oroza in conversation with Gean Moreno” Art Papers, May/June p.24.

GISH-artEcodesign/ Gli oggetti della necessità by Ernesto Oroza.

Curator: Allesandra Dini

Espacio provisional at Milwaukee International Art Fair 2008

The second Milwaukee International Art Fair arrived to the Polish Falcons beer hall, May 16-17, 2008. This location put amazing contemporary art from around the world against a backdrop of real old-world charm, in the midst of the quaint working-class Riverwest neighborhood. Strolling through the aisles provided a glimpse of new drawing, painting, video and sculpture while the sweet sounds of the Falcon Bowl rumbled up from the basement. The Falcon Bowl sports the 4th-oldest bowling alley in America, and for two days, possibly made the coziest art fair one could ever visit.

Espacio Provisional. Dark Fair at the Swiss Institute 2008

Sujetos invisibles at Museo Tamayo, Mexico. Nov, 2007. Info here

- Killing Time poster

- Enemigo provisional

- Agua

- Agua

- Agua

Curated by Elvis Fuentes, Yuneikys Villalonga, and Glexis Novoa at Exit Art, New York, May 12 – July 28, 2007.

Killing Time focused on the work of over 70 contemporary Cuban artists that approached the subject of time. “The Revolution has been a symbolic intervention on Cuban Time. In return, time has shaped discourses of and on the Cuban Revolution,” said the curators. Time patterns: Rewriting History, Productive Journey vs. Free Time: From Diversion to Subversion, and Aging and Decaying: An Archaeology of Utopia, were some of many subjects explored in different media, including performances, installations, photographs, videos, drawings, paintings, sculpture, murals, prints and ephemera. This exhibition spanned from the late 1970s to the present, and provided a timely context for Cuban artists whose work had little or no exposure in the United States. Many of these artists metaphorically recorded some of the tensions in the cultural, social and political landscape of the past three decades, and were often dismissed by the official discourse on the Island or stereotyped by narrow conceptions of identity. A special section of the exhibition featured the origins of Performance and Conceptual art in Cuba, through original works and documentation materials never before shown in the United States.

Events: May 13, 2007, a panel discussion with Glexis Novoa, Rafael Lopez Ramos, Ruben Torres Llorca, Maria Magdalena Campos Pons, Tania Bruguera, and Leandro Soto; a Cuban dinner provided by Havana Nights; and live performances by Tania Bruguera, Juan-Si Gonzalez, Alejandro Lopez, Maritza Molina, El Soca and Fabian Leandro Soto;June 16 and June 23, 2007 , Tropical Area, an evening of performances by the Trickster Theater featuring works by Rob Andrews, Eun Woo Cho, Saeri Kiritani, Julia Mandle, Oleg Mavromatti, Jolie Pichardo, Pasha RA, Boryanna Rossa, Rafael Sanchez with Jesus Sendòn and Aki Sasamoto

Publication: The catalog for Killing Time, placed in a unique box, includes a 74-page book with four essays in English and Spanish by the curators (Elvis Fuentes, Yuneikys Villalonga and Glexis Novoa) and Exit Art Co-founder/Cultural Producer Papo Colo; a DVD with video documentation of the exhibition; a DVD of the Trickster Theater performance Tropical Area; color reproductions of each of the artists’ works.

Read more:Killing Time Artforum (periodical) by Morgan Falconer, July 12, 2007.It’s difficult to suggest curatorial distinction and narrative development when you’re organizing an exhibition for Exit Art’s capacious, hangarlike space. The problem is exacerbated when you work with over eighty very different artists. For this exhibition, curators Elvis Fuentes, Yuneikys Villalonga, and Glexis Novoa present Cuban artists, some of whom are exiles in New York and Miami and some of whom remain at home. Rather than imposing rigid order, they instead set the mood convincingly with a few large-scale works and then sensitively juxtapose similar pieces along the nearby walls.Fidel Castro is a recurrent, ghostly presence: One imagines him in the seat of Alejandro Lopez’s Bunker of Thoughts, 2006, a booming public-address system that resembles a gun emplacement. And the show’s theme—the sense of hiatus he has created in Cuba—is elaborated in various works: In Rigoberto Quintana’s Cuban Calendar, 2007, the leader presides over every year since the revolution, yet the picture, the same each year, is of an elderly, maybe even dead Castro, lying horizontal against a bloodred backdrop. Given the dominance of national politics in our conception of the island nation, it is surprising how few other works address the topic. Instead, we see only its effects: Liudmila Velasco and Nelson Ramirez’s photographic sequence Those Who Are No Longer Here, 2004–2006, depicts the homes of departed friends. We also see artists responding to familiar concerns like feminism: Maritza Molina photographs a nude woman hauling a cart full of suited men through a field in Carrying Tradition #2, 2005. Taken as a whole, the exhibition is revelatory and intriguing. One only wishes a catalogue had accompanied it, to lend a greater sense of order and context.UN CAOS ILUSTRADO (Made in Oroza)

PARA UN DISEÑO IMPOSIBLE

Héctor Antón Castillo

“El arte no se hace, se encuentra”. Charles Simic

Ernesto Oroza (Ciudad Habana, 1968) pudo llegar a la conclusión de que su inventiva nunca superaría a la de quienes hacen arte contemporáneo sin recursos estratégicos para vivir a expensas de los conflictos que no padecen. Atrás quedaba la ambición por cristalizar la pieza autónoma o emblemática. La decisión se impuso al reto de emprender una veloz carrera. Dispuesto a comenzar un trabajo en solitario, Oroza devino en un trotamundos de la ínsula para registrar la diversidad de la filosofía del invento cubano. Su actitud lo llevó a coleccionar objetos útiles e inservibles, captar situaciones emergentes o lucrativas en los márgenes urbanos y, por supuesto, contaminarse del imaginario barroco popular. Este quehacer visual ilustra cómo una manufactura rústica puede generar un producto estético dotado de singular belleza. Todo para concederle a la supervivencia del diseño, en medio de la provisionalidad, un sesgo antropológico que el artista insiste en potenciar.

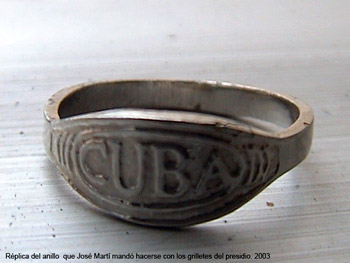

Ernesto Oroza. “Anillo”. 2003

Réplica del que José Martí mandó hacerse con los grilletes del presidio.

El origen de esta elección se remonta al año 1994. Cuba atravesaba una crisis económica identificada oficialmente bajo el rubro de “periodo especial en tiempo de paz”. Como diseñador profesional y ciudadano sin privilegios, Oroza se propuso darle una respuesta artística a una situación que estremeció a la Isla. Sus “objetos de la necesidad” representaban un panorama de carencias vivenciado por muchos e ignorado por quienes no lo sufrían en carne propia. Pero la eticidad de esta “operación de rescate” se torna irónica. Es innegable que son artefactos “alegres, desenfadados e inteligentes”, aunque tampoco debemos obviar que están asistidos por un impulso de obligada e impostergable “tarea de choque”; Divertimento para unos y embarazo para otros. El diseñador-artista valida ese derroche de ingenio doméstico como una alternativa a las demandas fabricadas por el mercado que sustentan al diseño contemporáneo.

En su Declaración de necesidad (2005), Oroza afirma: “Verdaderamente necesitar es ser, potencialmente, más dignos y libres“. Sin embargo, ¿Qué puede significar este postulado utópico para una persona sin ambiciones creativas que sólo añora la posibilidad de consumir sin que ello requiera un esfuerzo mental? A través de observaciones donde se mezclan lo romántico y lo pragmático, las teorías ilustradas de Ernesto Oroza intentan desmontar esas memorias del subdesarrollo que salen a relucir hasta cuando se disfruta de algún respiro material. Entre la concreción de vuelcos radicales y el goce de placeres mundanos, el cubano-promedio escoge la segunda opción. Como rastreador de “hacedores con obras pero sin carrera”, Oroza recorre un trayecto en forma de espiral que, finalmente, retrata el contexto social donde la ilusión de cambio es tan sólo una ilusión.

La esencia del hombre común es la apariencia que revelan estas documentaciones fotográficas. No obstante, lo que se legitima como producto visual no es la epopeya del caos, sino el detalle o la suma de fragmentos que contribuyen a propiciarla. Sólo así adquieren sentido un trapo rojo encima del televisor para protegerlo del mal de ojo o una campana para aviso de agresión aérea compuesta por un balón de oxígeno y una llanta de camión. Entre la superstición generada por el quiebre de la economía familiar y la paranoia naïf ante el inminente ataque enemigo, la propuesta de Oroza es algo más que un interés de plasmar la relación del sujeto urbano con su universo objetual. Por ello, el barniz chistoso de ciertas imágenes no consigue escamotear el drama real que encierran: El dilema de los países en vías de desarrollo anclados en su condición periférica.

En esta proposición, la frescura y sencillez de la forma de presentación cohabita junto a la densidad psicosocial de las imágenes. Aquí se apuesta por el documental decorativo regido por una libertad expresiva increíblemente orgánica. Dicho proceder roza en ocasiones el efecto kitsch, al recoger esas soluciones delirantes que recuerdan a Samuel Feijóo. Oroza reconoce la condición marginal del poeta, pintor e investigador de tradiciones locales como su influencia decisiva. Feijóo publicó antologías en las que recopiló el folclore rural del centro de la Isla con sus refranes, dicharachos, trabalenguas y décimas. En su variante urbana y mediática, esta secuencia de “enunciados sociales” continúa la indagación del maestro autodidacta que hizo un aporte valioso al legado de la cultura popular.

A partir de “un modo de existir que convierte el estado de tránsito en un momento eterno”, este curador del museo imaginario de la resistencia tropical concibe la noción de desobediencia tecnológica mediante el concepto de hibridación. Según anota Oroza: “Nada hay más irreverente que un camión-barco, una lavadora cortadora de col, un ventilador-teléfono o un jardín de envases“. Si la crisis “transitoria o provisional” se mantiene, los cubanos sensatos deben acudir a la irreverencia como sustituto de la rebeldía. El afán de suavizar una carga doméstica o de embellecer un hogar a bajo costo abarca un imperativo mayor: El anhelo de consumir la energía de la libertad sin que ello determine una inclinación por el desacato político frontal.

Este hibridismo tecnológico estimula la creación del “hombre nuevo” que accede a lo global con un simple gesto local. Al predominar la intuición en menosprecio de la razón, los excluidos de la nomenclatura del confort prefieren el alivio momentáneo o escapar para siempre. La desobediencia tecnológica es una manera de sugerir cómo la capacidad de renuncia es proporcional al espíritu creativo forjado en la conciencia de los sujetos vaciados del instinto de rebelión y sumidos en la pobreza.

La anarquía de la identidad portátil como salvoconducto de “armonía y seguridad” no puede restituir la esperanza de configurar un diseño siguiendo las coordenadas de estas locuras de sobrevivencia. El “todo es un invento” nunca se equipara al “todo es posible” ni siquiera en un plano simbólico. En un mundo donde “todo es ramita y hojas”, apenas se alcanzaría concretar una “estética de la desaparición”, pues “da lo mismo tomar un motor de lavadora para construir un ventilador, que ponerle un motor japonés moderno a una bicicleta norteamericana de principios del siglo pasado”.

El sueño de Oroza por demostrar la existencia de un diseño “bajo presión” engloba su propia pesadilla. Aquí radica la contundencia socio-artística de un proceso de búsqueda donde cada hallazgo implica una ambientación forzada.

Rasgando “sin querer” la piel de estampas costumbristas, Oroza alude al vicio de consumir el embrujo político de la Isla como una postal turística. En cambio, al registrar las “interioridades de la carencia” no persigue detonar panfletos impronunciables. A pesar de coquetear con la política en apariencia, la esencia de la maniobra insiste en desmarcarse del compromiso político. ¿Se reduce el compromiso político a sus precarias formas de decoración como alguien podría catalogar el activismo lúdico del artista suizo exiliado en Francia Thomas Hirschhorn? No hay denuncia explícita al revelar el trueque de la miseria colectiva en un negocio individual. Este fenómeno capaz de ser universalmente local es una forma de asumir la inmediatez contextual como un simulacro donde la ambivalencia permite salvar el arte y la vida.

Sin aspirar a la etiqueta de “instalacionista puro”, Ernesto Oroza ha documentado injertos visibles en una arquitectura donde la transformación parcial suplanta a la reconstrucción total. En este sentido, el desvelo por conquistar el espacio museográfico se revierte en la gestión de sustituir el “object trouvé” por la “situación encontrada”. Sin embargo, muchos de estos arquetipos sociales de un lugar específico podrían reemplazar a las cercas y taxi-limusinas de sus antiguos colegas delGabinete Ordo Amoris, intervenciones en las que desaparecían las fronteras entre el arte y la vida. Un ejemplo de peso son los tanques de agua colocados por los mismos inquilinos de un edificio (2005). Esta lección de “emergencia vital” pudiera engrosar las páginas de un libro de cualquier megaevento de arte contemporáneo.

Ernesto Oroza.”Parqueo” Fotografía fija de video de automóvil saliendo durante 8 minutos de un parqueo improvisado. 2004

En su diario de lectura, José Lezama Lima esboza el germen de un refinado invento: “La hipertelia es un fenómeno que rebasa su finalidad, una decoración“. Para el escritor cubano detenido en un sillón tras la ventana, la sobreabundancia o desmesura del maquillaje urbano era la tabla de salvación para un pueblo que cumplía su destino en el estruendo de las carrozas y comparsas ebrias del carnaval. De ello se deriva el “movimiento trocado en quietud” de una iconografía de contención, emplazada para domar los extravíos de la ciudad.

Salvando las distancias entre mito y realidad, Lezama y Oroza parecen compartir una fascinación simbólica por los leones de piedra y las fuentes. Ambos creadores detectan la presencia de una “metáfora tangible” que se desplaza de lo cultural a lo político: Urge construir una “terapia de la apariencia” para frenar la violencia de naciones tan indigentes como irrespetuosas. La vigencia de la intuición lezamiana le concede a la detención del tiempo la máxima responsabilidad dentro de la ciudad reinventada gracias a un proceso latente de pseudos-invención visual.

A fuerza de interrupciones, azares o premuras, Oroza insiste en contar una historia. Desde su naturaleza confusa, el absurdo de episodios reales prolonga la cadena de equívocos. Una muestra de ello se “dramatiza” al filmar la escena de un auto tratando de salir de un parqueo improvisado. Si el video ilustra la paciencia del conductor del vehículo lidiando con el área disponible ¿Qué sentido tendría alegar que este “accidente rutinario” facilita el paralelo entre un embotellamiento en la Ciudad de México y un nuevo Sísifo atascado en La Habana?

¿Entonces lo grande de un “máximo esfuerzo” se hermana con lo pequeño de un “mínimo resultado” para fulminar las diferencias entre centro y periferia? Una interrogante tan exagerada funge de alerta para evadir esas recepciones fantasiosas que abundan en la crítica de arte contemporáneo. Este “encierro pasajero” de “matiz cómico” reafirma una tesis manejada por el artista: Superar la fatalidad con ingenio no enaltece al hombre luego de convertir su “paso de avance” en un remake indeseable.

Los videos-fantasmas de Ernesto Oroza sirven de enlace entre la imposibilidad de producir un arte high tech con tecnología de punta y el anhelo de sedimentar un diseño Made in Cuba. Ellos fingen parodiar la pose cult del artista con instintos ancestrales privado de un mecenazgo experimental que soporte el rigor técnico de sus proyectos. La “finalidad primitiva” se iguala a la “finalidad mediática” cuando filma casas de aspecto doméstico, para después quitarle puertas y ventanas valiéndose de recursos digitales elementales. Devenidas en “piezas-módulos escultóricos”, las “viviendas selladas” aparentan una sátira a esa tradición del socialismo cubano de la restauración futura. Su veracidad simbólica radica en el hecho de simular una modificación estética mediante la acción de clausurar sin restituir, silenciar en lugar de instaurar.

Esta especie de “nihilismo manipulador” evoca los cortes arquitectónicos de Gordon Matta-Clark de los años setenta. Si era una causa perdida mejorar el estado de los “no-lugares”, solo restaba provocar la “anulación total” para llamar la atención sobre lo que no sería admitido o resuelto por las autoridades metropolitanas neoyorquinas. Thomas Crow observa en el experimento de seccionar edificios abandonados “una melancólica poética del oprobio”. Contrario al vandalismo romántico de Matta-Clark, el acto de Oroza adolece de un tono contestatario de intervención clandestina. En su caso, todo se limita a la animación silente de una costumbre estatal: Sellar para “dejar caer” una pregunta: ¿Por qué conservar las puertas y ventanas en una ciudad que debe trascender la obsesión de mirar hacia el exterior de sus muros?

Lo que ahora se presenta es un esbozo de “arte público” que no invade el “afuera” sino el “adentro” del espectador consciente. Pensar la ciudad no significa el ansia de trastocarla negociando con las instancias hegemónicas. La única pretensión de Ernesto Oroza estriba en ser un “cronista procesual” de esa memoria colectiva expuesta a desaparecer. En esta visión interactiva de lo cubano, la angustia neutraliza el choteo de ese imaginario popular donde “hasta el muerto se va de rumba” como ocurre en un pasaje de la narradora y folclorista Lydia Cabrera. Existe la creencia de que en Cuba la vida todo lo transfigura: Ríos y piedras, máscaras y dioses, caracoles y cementerios. La razón poética de Oroza aspira a testimoniar ese factum de la Isla que obsesiona a quienes la palpan de cerca o la vislumbran desde lejos.

Esta producción visual reflexiona en torno al sentido de la imposición contemporánea. Sus eslabones dispersos conforman esas minúsculas historias que definen a la gran historia de la metamorfosis diaria de la disciplina-bloqueo en creatividad, la médula caótica en mascarada festiva, el desencanto individual en amnesia masiva. Entre simulacros de proyectos y manifiestos, el voyeur con manía de ensayista deberá proseguir su dinámica investigativa en el laberinto de las ciudades hasta que pueda declarar con vehemencia el motivo de su silencio: “Ya no hay dolor en mi obra“.