Archetype: the original pattern or model from which all things of the same kind are copied or on which they are based.

As Ernesto Oroza began his work on Archetype Vizcaya, we invited him to look closely at the estate. For several months, he examined the patterns of materials and the movements of crowds and individuals, including party planners and curators; he opened every closet and catalogued visible and invisible surfaces; he explored the archives and original designs for the property; he moved across the line that separates the public from what is behind the stanchions and the plexiglass; and he studied Vizcaya’s presence on the Web.

For several years, Oroza has been interested in utilitarian objects and vernacular practices of appropriation, in which things are taken from their original context and given new purpose and meaning. As an extravagant Italianate vacation home designed for millionaire James Deering by artist and interior decorator Paul Chalfin, Vizcaya would not appear at first sight to be remotely touched by issues of necessity or by a vernacular approach to architecture and design. In fact, we invited Oroza because we were confident that his work in entirely different contexts would enable him to see Vizcaya with fresh eyes, helping us to understand how the estate is currently “used” by its visitors and to envision alternate ways of “using” it.

Oroza developed tools that engage us in looking at this National Historic Landmark with an active, playful and ironic perspective. At the same time, in exploring the dynamics of cultural appropriation, Oroza raises issues at the core of Vizcaya’s history and cultural significance. So too does he present Vizcaya as an ongoing layering of appropriations, histories and meanings, still vibrant and more unpredictable than ever.

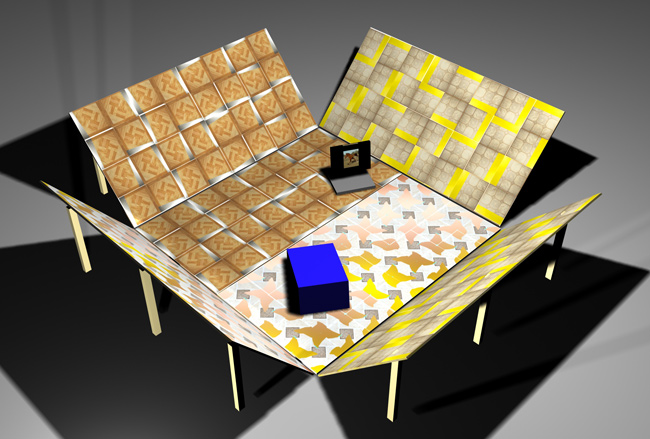

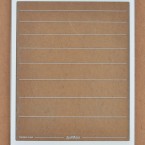

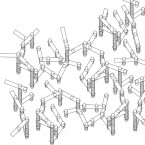

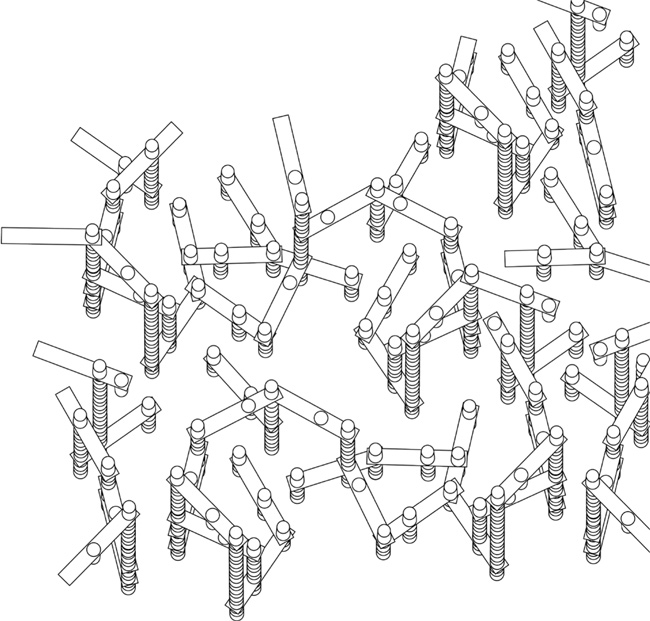

A key component of Oroza’s project is a printed “map” of the Main House. This map is far from a literal floor plan, but rather an abstract guide that invites visitors to discover objects and ideas generally unseen or overlooked. The extravagant floors assembled by Chalfin serve as the organizing principle. On one part of the map, the floors are catalogued as a means to identify the different spaces at Vizcaya; and the floors are associated by numbers to images of objects in the rooms that they adorn. The map directs us to look at the surfaces beneath our feet and, in doing so, breaks our normative viewing habits and frees us to participate in an intensive treasure hunt for curious artifacts. Oroza’s map is an object in its own right that can be taken home and enjoyed as a piece of art or wallpaper, or in any way one wishes.

Visitors using the map to explore Vizcaya will find traces of Oroza’s intervention and interpretation in unexpected places around the house. On the plexiglass, for example, Oroza has inserted silhouettes of the invasive plants that endanger Miami’s local vegetation. By introducing “alien” things into the fabric of Vizcaya, Oroza challenges us to question what is original or authentic on an estate in which the buildings, landscape, furniture and art objects were all imported or invented.

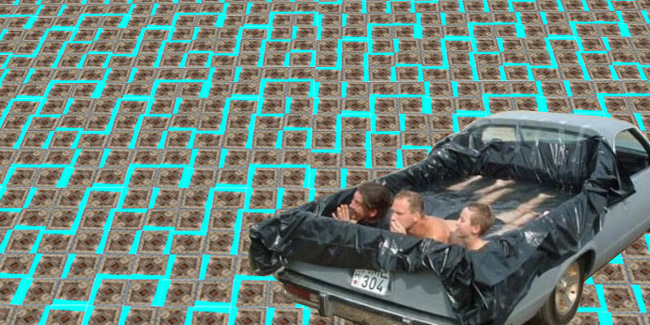

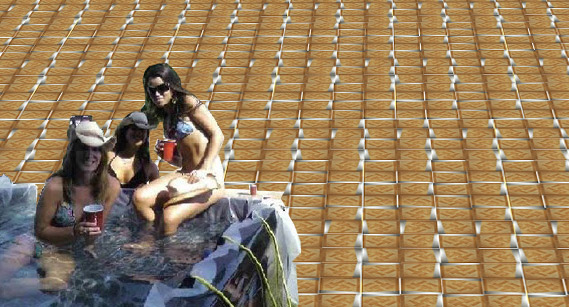

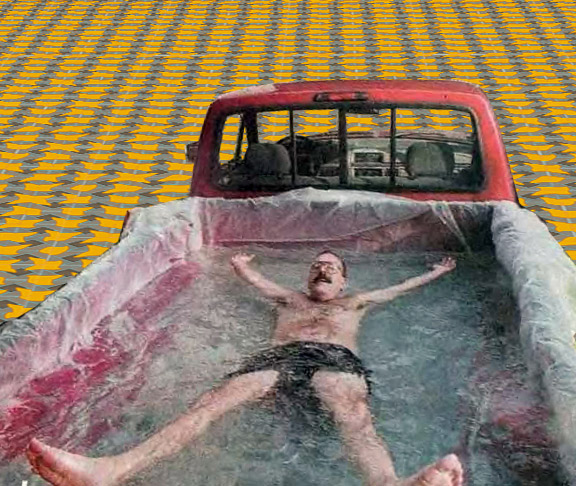

Ernesto Oroza also went outside of the estate’s walls to understand Vizcaya, scouring the Web for information. From this research, he assembled the third component of his project, a catalogue of amateur videos of quinceañeras, weddings and other parties at the estate. To immerse oneself in this kaleidoscope of moving images is perhaps the best, and certainly the most entertaining, way to understand how Vizcaya is “used” by its visitors.

With Archetype Vizcaya, Oroza explores the border between the institution and its appropriation by the public.

He creates new tools to experience Vizcaya’s spaces and to discover the unseen. Oroza causes us to contemplate what is “native” and what is “alien” in a museum context or in a social environment. And, he asks us to consider the relevance of a historic house filled with Italian decorative arts in modern Miami. But, most important, he shows us that if Deering and Chalfin could appropriate and reinvent Italian decorative arts and design almost one hundred years ago, we should feel free to appropriate and reinvent their work today.

Over the last few months, we engaged in ongoing conversation with Ernesto Oroza about Vizcaya and its multiple histories. The inside of this brochure includes excerpts of this conversation, which was central to the development of his project.

Flaminia Gennari-Santori, Deputy Director for Collections and Curatorial Affairs

Courtesy, Vizcaya Museum and Gardens

© Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, Miami, Florida. All rights reserved.

A conversation between Ernesto Oroza and Flaminia Gennari-Santori, Vizcaya’s Deputy Director for Collections and Curatorial Affairs.

EO: Do you think Paul Chalfin applied architectural historicism at Vizcaya because it was a culturally accepted “shortcut” or for other reasons?

FGS: Vizcaya is a product of its time, and architectural historicism is a crucial component of its aesthetic. But, at Vizcaya, historicism was used as the language for the fictional narrative of a country house that had been occupied for centuries and had graciously accommodated changes in taste and style. In fact, it was built over the span of just a few years as the theatrical set for the cultural projections of its owner, James Deering, and even more, of its designer, Paul Chalfin. One could look at the entire estate as the ideal portrait of a worldy, sophisticated gentleman, with the taste of a connoisseur and the means to surround himself with the ultimate technology. And yet, here and there, like in the sets of a period film, one finds the props, the joints of old and new, of “authentic” and “imitated.” Still, I believe that Chalfin had a further ambition: to reproduce the layering of styles and historical periods that he had learned to appreciate in Italy. The result was, of course, pure American eclecticism.

EO: What do you think are some of the most interesting objects for someone trying to understand Vizcaya?

FGS: One of them is certainly the statue of Mezzogiorno (“Midday”), which greets visitors on the driveway when they enter the property. This idealized representation of a Caribbean native —dressed as a classical soldier and symbolizing the passage of time—originally adorned a garden in the Veneto. At Vizcaya, it was placed in its preeminent position as an evocation of a mythical Caribbean and, thus, for me, Mezzogiorno synthesizes Vizcaya’s multiple layers: 18th-century Venice and the early 20th-century culture of appropriation and reinvention that created the estate. In the house, one of my favorite objects is the system of shelves on the east wall of the Living Room. It was created in central Italy in the mid 16th-century as a church screen. Paul Chalfin cut it into pieces, added some surreal neoclassical urns and transformed it into a display case for “collectibles,”an indispensable element in the house of a gentleman. Yet, the “collectibles” are the least interesting things: partly hidden by the structure, one can find beautiful, tragic wood carvings of men fighting with demons, of medallions with monks’ profiles, of human figures with clawed hands. A house designed for relaxing and entertaining hides these daunting and moving figures.

EO: I find the plexiglass panels in the house quite interesting, because I see them as a vernacular intrusion into the history of Vizcaya. I think that the plexiglass can be interpreted as the validation of certain surfaces, a curatorial decision imposed by preservation specialists to protect things of historic value from museum visitors. How do you see them?

FGS: I think that the placement of the plexiglass at Vizcaya is one of the most curious sub-narratives of the house. Why we find a panel in front of a plain wall, and not protecting the 18thcentury lacquer door next to it, is a m ystery that entirely defies me. The plexiglass is another layer in Vizcaya’s history that you are bringing to our attention by including it in your project. Like the canopy, the plexiglass marks the conversion from private home to public museum, a transition that understandably generated anxieties of control and institutional identity.

EO: The eccentric character of a Baroque retreat on Biscayne Bay must have seemed far more powerful without the Courtyard glass canopy, when the house was exposed to natural forces such as wind, rain, hurricanes, saltwater and mosquitos. Do you think that the museum’s collection and activities could be sustained if the canopy were removed?

FGS: The canopy is the most aesthetically intrusive consequence of the transformation of Vizcaya into a public museum. The Main House was conceived as a pavilion immersed in nature, where the sky and the sea could be seen from every room. The most interesting challenge of a house museum is that it forces you to balance on the thin and slippery ridge between the public and private realms. The canopy exemplifies this challenge. We are about to commission a new one and our goal is to make it as light and invisible as possible, while protecting the collection and keeping the heart of Vizcaya comfortable for the public even during the summer. I agree with you that the glass canopy compromises Vizcaya’s magic, yet in order to stay alive, places need to subtly adapt to time.

FGS: And now I’d like to ask you a question. With Archetype Vizcaya, you unveil a new geography of the place, which reflects both your own approach as an artist and designer and the very thorough research you conducted on the estate and its history. How did your desire to “re-map” what is already historic come about, and what do you hope visitors will take away from the tools you have provided?

EO: My answer would explain not only this project, but my practice in general. In my work, I have developed an analytical structure, a diagram that is almost immutable, with spaces or variables that are filled in by the context I study. It’s a system of ideas and convictions structured by my inquiries into material culture, need, design, languages, and radical and experimental architecture. Yet, the content that fills the equation—the context—ends up affecting the work. This is what happened with Archetype Vizcaya: my model came face-to-face with the structure and the interrelationships of Paul Chalfin’s interior design. I found some recurrent behaviors here and thought that it might be important to reiterate them. The patterns of appropriation and permutation have been so present at Vizcaya from its very origin, that I believe they’re inevitable. Vizcaya has been dissolving into Miami since its construction, due to the climate, changes in function and its relationship to the community. To me, it is interesting to sit back and watch this process. It’s like adding pigment to a river and watching it dissolve into the sea. The map, the provisional gallery on the plexiglass and the video archive are all moving in this direction, and are abstract tools that can be employed anywhere; but, at Vizcaya, they can provoke very specific results.