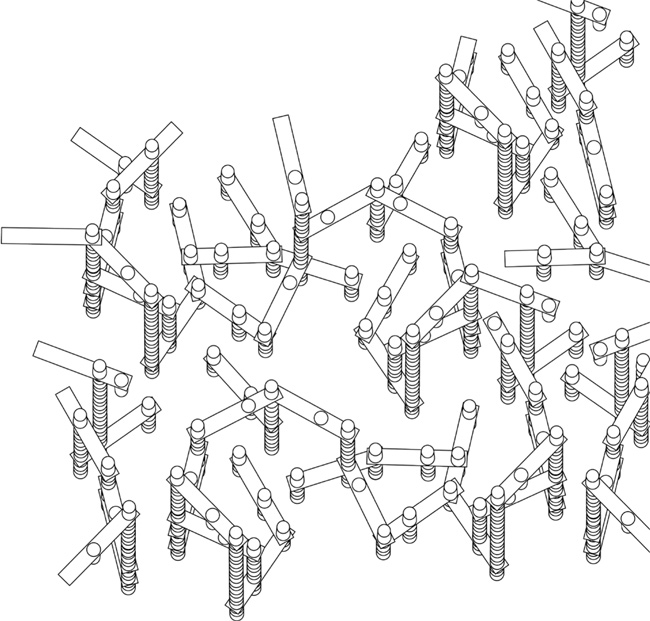

Crystal Radio (Radio a Galena), 2011. Ernesto Oroza, Gean Moreno.

“Radio a galena” is an rudimentary crystal radio that function without a conventional power source. They are housed inside milk crate casings which are then stacked in towers. Early versions of the modern radio as we’ve come to know it, Crystal Radios convert electromagnetic radio waves into alternating electric currents.

Critical Strategies of Post-Utopian Cuban Art (Cuba-United States). Curated by Adriana Herrera

Houston Fine Art Fair, Sept. 15 – 18, 2011.

The exhibition—featuring Consuelo Castañeda, Rubén Torres Llorca, Glexis Novoa, Ernesto Oroza and Gladys Triana—includes pieces (or re-mades) belonging to the period in which they lived on the island, and challenged the hegemonic system, along with artworks that are particularly strong in the production of a critical—and political, in a more general sense—vision of the United States. The exhibition is curated by Adriana Herrera, Miami-based independent curator and critical writer, and sponsored by Hardcore Contemporary Art Space, located in booth 602.

ARE YOU AN ARTIST IN NEED OF FAST CASH?

Forget gallery hassles GET CASH NOW! High! Fast! Immediate cash payments!

Come on down today!

Pawnshop at Thessaloniki Biennial

18 September–18 November 2011

Typou 5

54625

Thessaloniki

Greece

Opening hours:

Wed/Thu/Sat/Sun 17:00–21:00, Fri/19:00–23:00, Mon–Tue: closed

T 30 2310522672

pawnshop@e-flux.com

www.thessalonikibiennale.gr

Originally established by artists Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle in New York in 2008, PAWNSHOP went bankrupt at the beginning of the world financial crises, only to re-open successfully in Beijing and, most recently, at Art Basel.

Structurally, a pawnshop is a short-term loan business, which retains a collateral object (a camera, a ring, a guitar, a gun, and in this case an artwork) in exchange for a cash loan—a small fraction of the object’s value that needs to be repaid with interest within a one-month period. If the owner of the pawned object does not return to collect it and repay the loan + interest within 30 days, the pawnbroker has the right to sell it.

What is of particular interest in pawnshops is the peculiar mixture of the illicit and the desperate, futurity and anticipation. The idea that the object is collateral for cash that might be traded back for the object during a set duration, could be put in other words, that works of art and money are just dancing in a choreography in which they might just circle back and meet again, and cancel each other out, but in fact rarely do.

All profits from PAWNSHOP have been donated to Doctors Without Borders.

PAWNSHOP Inventory: Lucas Ajemian, Armando Andrade, Florian Aner, Artemio, Michael Baers, Christin Berg, Bik Van Der Pool, Julien J. Bismuth, Chloe Briggs, Mike Bouchet, Svetlana Boym, Francois Bucher, Andrea Büttner, Etienne Chambaud, Herman Chong, Branka Cvjeticanin, William Diaz, NICO DOCKX, Gardar Eide Einarsson, Annika Eriksson, Köken Ergun, Jakup Ferri, Jean-Pascale Flavien, Harrell Fletcher, Iris Flügel, Egan Frantz, Peter Freidl, Jaime Gecker, Carmen Gheorghe, Barbad Golshiri, Sara Greenberger-Rafferty, Antonia Hirsch, Klara Hobza, Ralf Homann, Sejla Kameric, Matt Keegan, Christoph Keller, Staš Kleindienst, Runo Lagomarsino, Andriana Lara, Annika Larsson, Sebastjan Leban, Kit Lee, David Levine, Liz Linden, Nuno daLuz, Rodrigo Mallea Lira, Lucas Moran, Gean Moreno, Shane Munro, Sina Najafi, Trine Lise Nedreaas, Carsten Nicolai, Lisa Oppenheim, Ernesto Oroza, Bernardo Oritz Campo, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Marion von Osten, Olivia Plender, Bettina Pousttchi, Khalil Rabah, Manuel Raven, Fay Ray, Joseph Redwood-Martinez, Anri Sala, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Julia Scher, Jessica Sehut, Matt Sheridan Smith, Aaron Simonton, Shelly Silver, Lucy Skaer, Michael Smith, Nedko Solakov, Francesco Spampinato, Peter Spillman Franz Stauffenberg, Eric Stephany, Martin Stiehl, SUPERFLEX/ COPYSHOP, Jalal Toufic, Andra Ursuta, Gabriela Vainsencher, Costa Vece, Lawrence Weiner, Ana Wolovick, Haegue Yang, Florian Zeyfang, Andrea Zittel

New works by:

Andreas Angelidakis, Uri Aran, Athanasios Argianas, Manfredi Beninati, Carolina Caycedo, Christina Dimitriadis, Jimmie Durham, Irini Karagianopoulou, Apostolos Kotoulas, Nikolaj Larsen, Carlos Motta, Theofanis Nouskas, Angelo Plessas, Mathilde Rosier, Tayfun Serttas, Socratis Socratous, Chryse Tsiota and others.

Forget the market! Forget the fair! Dollar is Low! Recession is Back!

It’s time to shop… PAWNshop!

***

”Old Intersections-Make it New”

3rd Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art

Thessaloniki, Greece

18 September–18 December 2011

Opening:

September 18, SMCA, Moni Lazariston, 19:30

www.thessalonikibiennale.gr

Critical Strategies of Post-Utopian Cuban Art (Cuba-United States). Curated by Adriana Herrera

Houston Fine Art Fair, Sept. 15 – 18, 2011.

The exhibition—featuring Consuelo Castañeda, Rubén Torres Llorca, Glexis Novoa, Ernesto Oroza and Gladys Triana—includes pieces (or re-mades) belonging to the period in which they lived on the island, and challenged the hegemonic system, along with artworks that are particularly strong in the production of a critical—and political, in a more general sense—vision of the United States. The exhibition is curated by Adriana Herrera, Miami-based independent curator and critical writer, and sponsored by Hardcore Contemporary Art Space, located in booth 602.

Nektar De Stagni and Gallery Diet are pleased to announce a new collaborative project:

Hard Poems in Space

Opening September 8th 2011, 7 to 10 pm

Bhakti Baxter, Paola Pivi, Gean Moreno, Ernesto Oroza, Christy Gast, Jim Drain, Martin Oppel, Daniel Milewski, Agathe Snow, Emmett Moore, Rene Gonzalez, Fabienne Lasserre, Nektar De Stagni, Confetti System, Dennis Palazzolo, Aranda/Lasch.

The project, which began during the summer of 2011 through a series of workshops at NDS (Nektar De Stagni Shop) and Gallery Diet, was conceived in order to bring together invited Artists and Designers to make functional objects. Participants are working collaboratively or individually, but with the goal of creating an overall exchange between different practices, as well as to create a cohesive and interactive social environment, to open on Fashion’s Night Out on September 8th, through December, 2011, at the NDS

Design District Space.

Nektar De Stagni Shop

155 ne 38th St.

Miami Design District.

Open Daily 11am to 6pm

786 556 3033

WWW.NEKTARDESTAGNI.COM

info@nektardestagni.com

Ernesto Oroza: el espacio relacional de todas las cosas del mundo

ADRIANA HERRERA

Ernesto Oroza (La Habana, 1968) exhibe actualmente la muestra de videos y fotografías Enemigo Provisional en Art@Work. En 2007 obtuvo la beca Guggenheim por su proyecto Arquitectura de la necesidad que indagaba en la reconfiguración ocurrida en el interior y exterior de los hábitats de La Habana. Tras graduarse de diseñador industrial durante el Período Especial había enfrentado la imposibilidad material de producir obras sofisticadas y descubrió en cambio que existía un impresionante “período de diseño popular masivo”, según escribió el crítico y artista Gean Moreno, con quien ha creado obras colectivas explorando un similar tipo de práctica en el Little Haiti de Miami.

Viendo su oficio sobrepasado por un entorno en el que la gente trasformaba sus viviendas con inesperadas envolturas o modificaciones inusuales para resolver la escasez habitacional; y en el que también se fabricaban objetos con lo que había a mano, improvisando soluciones frente a la carencia; renunció a sus ideas académicas para absorber las prácticas de la estética y vida popular.

Se convirtió en un “ex diseñador” –como lo llamó Moreno, apropiándose del término acuñado por Martí Guixé-, que más que crear, acopia objetos de arte encontrados que fotografía, usa como patrones, o como ingeniosas instalaciones de solución espacial fabricadas con recursos “pobres” como baldes, cajas de cartón, piedra o plástico. Pero sobre todo, funcionan como artefactos de pensamiento para revelar zonas de interrelación en sombra.

Su práctica artística refleja cómo la necesidad puede propiciar en Cuba el despliegue de una recursividad orgánica, marcada por los ritmos y las urgencias de la gente. Pero lejos de caer en el romanticismo que hace exóticos esos objetos caseros ingeniosos – una lámpara de querosene hecha con una botella de leche-, reafirma que no se renuncia al deseo del objeto “verdadero”. Como un Aladino contemporáneo, Oroza cambiaba de hecho, un ventilador nuevo por el que alguien había creado con un disco de acetato para “resolver” su carencia, y lo usaba como un readymade de la arquitectura de la necesidad.

Oroza demuestra hasta qué punto diseño y arquitectura, asumidos desde la supervivencia cotidiana, pueden desafiar la ética de un sistema que reprime la iniciativa individual, pero también la de otro que conduce a un consumo de cosas hechas y no necesarias a fin de someterlo a un omnipotente poder financiero.

Su obra no está en las piezas, sino en la intermediación social. Es una mirada apostada en los espacios emocionales –del deseo, del miedo a la escasez, de la posesión simbólica, de la necesidad de expansión- que se activan en las relaciones de las personas con los objetos y arquitecturas con los que viven. Su estética relacional se apropia de las prácticas populares para erosionar los lugares comunes que saturan las ideologías del poder.

De modo coherente con una programación ligada a la observación cultural de la migración y de los desplazamientos territoriales y de visión en Miami, Art@Work exhibe el video y las fotos de Enemigo Provisional. Las piezas registran el estado en que queda un set de objetos caseros tras ser usados en los campos de tiro improvisados que Fidel Castro autorizó montar con escopetas de cacería amarradas a una barra. El gobierno las suministró conminando a la gente a entrenarse a disparar para enfrentar la amenaza de una invasión imperialista. Los campos provisionales, creados para una espera hipotética, funcionan como negocios improvisados en estructuras donde se cuelga cualquier objeto inútil que pueda ser baleado. Balones desinflados, muñecas viejas, piezas sueltas, reciben una descarga de agresividad popular obviamente más conectada con la liberación de una energía de frustración social, que con su supuesto propósito de entrenamiento. Cada objeto agujereado y fotografiado cumple una función que desplaza la inmovilidad de una sociedad donde todos están a la espera de lo que no ha de venir, por una catarsis tan absurda o grotesca como el estado en que quedan estos blancos que hablan no sólo de la extensión del simulacro sino de las estrategias de desplazamiento. El “enemigo” externo provisional ayuda a acatar la inacabable espera.

Oroza propuso la “desobediencia tecnológica” como una vía para remover la inmovilidad que imponía en Cuba determinó una forma de vivir en la transición; pero también el perenne tránsito hacia el progreso que en el capitalismo acaba por obviar, en aras de una sofisticación tecnológica, “los paradigmas de vida humana”.

Otro video exhibido pertenece al archivo llamadoDesobediencia tecnológica y muestra la aparición de Fidel Castro intentando promocionar la ventaja de productos chinos para el consumo, en un momento en que masivamente la gente diseñaba con cualquier cosa objetos de necesidad. La reproducción de esa imagen del líder político que parece encarnar un vendedor callejero armando cuentos sobre el producto que intenta vender, evidencia el límite de las ficciones sociales y erosiona el poder discursivo de un sistema a partir de la visión de los objetos.

En síntesis, estas obras encontradas que interpelan los límites de las ficciones sociales, burlan los estereotipos de exaltación o detracción del consumo del comunismo y del capitalismo, y proponen la formulación de otra ética en la relación del hombre y las cosas.

ESPECIAL/EL NUEVO HERALD

Adriana Herrera es escritora, curadora, y crítica de arte. Colabora con galerías y museos, y asesora publicaciones especializadas.

‘Enemigo Provisional’ de Ernesto Oroza en Art@Work, 1245 SW 87 Ave. Hasta el 21 de septiembre. Charla del artista y visita guiada el jueves 15 a las 7 p.m.

adrianaherrerat@gmail.com

Junge Szene Kuba

Pasinger Fabrik. Munich, 10.06.2011 – 24.07.2011.

Curated by Siegfried Kaden.

ART@WORK PRESENTS ENEMIGO PROVISIONAL

Exhibition of Works by Ernesto Oroza

On View July 9 – August 31, 2011

Opening Reception: Saturday, July 16, 2011

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004, D-print, 5 x 7 inches & Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004, D-print, 8 x 10 inches.

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004, D-print, 8.5 x 11 inches & Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004, D-print, 8.5 x 11 inches

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

- Untitled. (from archive Enemigo Provisional). 2004

Provisional Enemy

Shooting galleries in Cuba are spaces traversed by a nihilistic ray. These are sectors of the city–and of the material culture of the island–in which destruction occurs at an accelerated pace. They are the dispersed centers from where the void radiates.

6 years ago I made a video titled Provisional Enemy. During the first seconds of the video, one reads: “On Tuesday, 26th of February, 2004, the person in charge of a shooting gallery agreed to sell me his work resources: a wire full of hanging objects that have been shot by dozens of Cubans, each day, with a pellet gun.”

A version of this video, photos from the archive “Enemigo Provisional”, and videos of Fidel Castro promoting household goods from Communist China in Cuban national television constitute the exhibition “Enemigo Provisional” at Artatwork.

Ernesto Oroza, 2011

Enter the Nineties

MIAMI-DADE PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM

June 16 – September 13, 2011

2nd floor exhibition space, Main Library, 101 W. Flagler Street, Miami

Reception: Thursday, June 16, 7-8:30pm

With special performances and a 14-foot inflatable moon courtesy of

MARILYN GOTTLIEB-ROBERTS and THE END

Read review by Anne Tschida

This summer, as part of its year-long 40th anniversary celebration, the Miami-Dade Public Library System remembers the 1990s. That decade was a memorable time for the Library’s summer art tradition: exhibitions organized around one simple, culturally-loaded object or theme–shoes, boats, the alphabet, food, landscape, sound, dogs—with broad participation from many artists. Enter the Nineties adopts that format by inviting artists, writers, librarians, and cultural producers from Miami and elsewhere to trade zines (independent, do-it-yourself magazines or fanzines) with the Library. The Art Services and Exhibitions Department made a 90s throwback zine called Poetry and Power and will exhibit all the zines received in exchange.

Although zine culture dates back to the 1930s or before, many people made, read, and traded zines as part of the flourishing zine culture of the nineties. Some say a zine renaissance is happening right now. The exhibition title comes from ABC No Rio: Enter the Nineties, a 36-page photocopied zine about the history of the New York art/punk squat ABC No Rio. The show includes permanent art collection work from past summer shows along with an extensive array of zines and a lounge area for reading them.

An ever-metastasizing list of participants includes Kevin Arrow, Bhakti Baxter, Mark Boswell, Domingo Castillo, Rosemarie Chiarlone with Susan Weiner, Adalberto Delgado with Maria Amores, Karl Engle, Cristina Favretto, Abel Folgar, Mickey Garrote, Marilyn Gottlieb-Roberts, Adler Guerrier, Patricia Margarita Hernandez, Jay Hines, Kathleen Hudspeth, Jose Isaza, Matt Keegan/North Drive Press, Sky King, Dina Knapp, Hamlet Lavastida, Jillian Mayer; the Society for the Preservation of Lost Things and Missing Time (Division of Letters & Papers) with Raul Méndez, Anonymous, Frank Wick, René Morales, Liz Rodda, Solomon Graves, Emily Ginsburg, Joe Biel, Trista Dix, Nick Lobo, Tim Curtis, and more; Gean Moreno, Brandon Opalka, Ernesto Oroza, Yaddyra Peralta, Jenni Person, Christina Petterson with Elijah Peck, Proyectos Ultravioleta, Alice Raymond, Brian Reedy with Peter Santa-Maria, Claudia Scalise, Barron Sherer, Marc Snyder, Carol Todaro with J. Tómas Lopez, Liz Tracy/The Heat Lightning with Venessa Monokian, César Trasobares, the TM Sisters + P. Scott Cunningham and Matthew Abess, Odalis Valdivieso, Angela Valella, Marcos Valella, Michelle Weinberg, Agustina Woodgate with Stephanie Sherman, and Barbara N. Young with Robert Huff.

For context, Enter the Nineties will also include artists’ zines and publications recently added to the Library’s permanent art collection such as seminal artists’ periodicals Avalanche, Art-Rite, and New Observations; a 1996 zine guide to the Internet published by Paper Tiger TV West; Amy Sillman’s The O-G and Nicole Bachmann’s Me and My Friends; Latin American zines Carne (Venezuela), Vestite y Andate and Colorin Buc (Argentina); image-based zines by artists Beni Bischof, Özlem Altin, and K8 Hardy; and zine collections belonging to Kevin Arrow (including a complete run of Mike McGonigal’s Chemical Imbalance), WLRN Under the Sun producer Trina Sargalski, and Oly Vargas.

For more information, see www.mdpls.org or contact Art Services and Exhibitions at 305-375-5048 or delgadod@mdpls.org .

Visit us on Facebook.

Pawnshop e-flux

Kopfbau Basel (twitter)

June 15–18, 2011

11:00–19:00

Facing the main hall at the Messeplatz, go to the red building next to Art Unlimited (to the left end of the fountain), look for the currency exchange and the kopfbau sign, enter through the time/bank.

e-flux has been invited to develop a special project for the Kopfbau during Art Basel. The Kopfbau (head building) is the oldest building in the Messeplatz complex, slated for demolition later this year. In response to this invitation, e-flux developed a constellation of projects situated somewhere between exhibitions of art and the concrete forms of sociality encountered in everyday life. Conceived as an independent universe with its own bar, hotel, shops, admissions, and so forth, this project operates in parallel, and as the inverse to the neighboring art fair: operating during alternative hours and in surprising and often paradoxical ways, and ranging in scope from the educational to playfully predatory and mercantile. Its component parts draw on a wide circle of institutions, artists, curators, and writers who have been involved with various e-flux projects over the past several years and comprise seven discrete projects, including:

Basel Pawnshop—both an exhibition and an artwork in itself, Basel Pawnshop mediates the complex choreography of art and money. As a fully functional pawnshop, it has an inventory of over a hundred art works, some made specifically for this occasion. Artists who have contributed to the Pawnshop include: Armando Andrade Tudela, Michel Auder, Michael Baers, Luis Berríos Negrón, Marc Bijl, Andrea Büttner, Annika Eriksson, Peter Friedl, Joseph Grigely, K8 Hardy, Christoph Keller, Annika Larsson, Kenneth Lum, Gustav Metzger, Darius Miksys, Gean Moreno & Ernesto Oroza, Bernardo Ortiz, Olivia Plender, Julia Scher, Tino Sehgal, Nedko Solakov, Eric Stephany, Jalal Toufic, Bik Van der Pol and Marion Von Osten among others.

A Guiding Light—Liam Gillick and Anton Vidokle stage and film Episode 2 of A Guiding Light, originally commissioned by the Shanghai Biennial and produced by New York’s Performa in 2010. The project combines a theoretical text by Franco Berardi (Bifo) with the structural analysis of a1952 episode of the television soap opera, Guiding Light, to stage a production that shifts between analysis and self-critique. Captured by several cameras, the resulting film preserves the soap opera’s signature stage blocking and repeated cuts, while highlighting the differences and difficulties encountered when attempting to capture the potential of art today.

Agency of Unrealized Projects (AUP)—a temporary office that exhibits a growing archive of several hundred unrealized art projects, comprising contributions received through an open call, as well those originally collated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and presented in the book Unbuilt Roads (1993). AUP presents works by Judith Barry, Heman Chong, Jimmie Durham, Yona Friedman, Philippe Parreno and many others.

Guesthouse Basel—a free, five-day residency for young artists, curators, critics and gallerists, organized in collaboration with Städelschule, Frankfurt, inspired by the legendary Gasthof event that took place in Frankfurt in 2004, during which Rirkrit Tiravanija and Daniel Birnbaum radically transformed the art academy into a free hotel for numerous young artists visiting Documenta in Kassel.

Time/Bank Currency Exchange—a Time/Bank outpost where time currency (designed by Lawrence Weiner) can be obtained in exchange for other currencies, biological time, ideas, services and commodities. Time/Bank proposes an alternative economy in which individuals and groups in the cultural fields can trade time, skills and commodities to get things done while circumventing money. www.e-flux.com/timebank

The Book Coop: e-flux journal & network—features art books, magazines and other types of publications from members of the journal network, a group of around 200 international art centers, art book stores and independent publishers that self-publish and distribute the print-on-demand e-flux journal.

Salon Aleman (the return!)—a rooftop bar inspired by the original Salon Aleman, the basement bar that operated from 2006–2007 in the basement of Unitednationsplaza, Berlin.

- Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Untitled (decoy), 2010. Wood and found tiles. Functional object 48” x 48” x 12”

- Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Untitled (decoy), 2010. Wood and found tiles. Functional object 48” x 48” x 12”

- Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Untitled, 2009. Cushings, T-shirts and refills, 16×16 in each

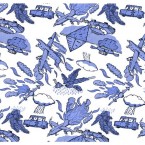

- Tonel. Telarte pattern for Tabloid 8, 2009. newspaper

- Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Studio Scrap Stools 2, 2010. plywood

- Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Untitled, 2010. Newsprint and printed matter

TABLOID #8: This tabloid was produced by Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza for the exhibition DECOY. Farside Gallery 2010. Miami, FL.

Textile pattern by Tonel, mass produced as part of the cultural initiative TelArte, Havana 1987, altered by Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza, 2010.

Special thanks to Tonel for allowing us to use his work.

8 pages. Blue. Edition of 1000

From press release:

(Miami, FL) -For the exhibition Decoy, Ernesto Oroza and Gean Moreno are producing an abstracted interior in the guise of a reading room. In it, nothing is what it seems: a graphic/decorative figure is actually a schematized image pulled from a partially successful effort to join art and mass production (TelArte); the typology of a bench is folded into that of a table which, in turn, is folded into that a display structure; a set of funky tiles stand in as shorthand diagrams of procedures witnessed at the local salvage yard from where they were reclaimed; a tabloid (as a medium for information distribution) is inseparable from a wallpaper as a decorative structure, but the wallpaper presents its own non-decorative information; cushions sewn out of old T-shirts double as a starting archive of graphics that have taken root in our vernacular landscapes. Things acquire two and three identities and negotiate precarious balances between them. Somewhere in all this, one can begin to discern what is important to Oroza and Moreno: crisscrossing functional patterns in order to produce astute artifacts; testing the possibility of objects feed on tactical logics which, despite their proclivity for tending to the necessary with impressive economy, are all-too-often relegated to one kind of margin or another; formulating tentative theorems on what possibilities are still viable and vital for object production and urban experience.

Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza. Untitled (decoy), 2010.

Wood and found tiles. Functional object 48” x 48” x 12”

see exhibition images here

(english version):

Farside Gallery. Miami

by José Antonio Navarrete / Arte Al Dia International, July 2010

Decoy, the exhibition of works by Gean Moreno and Ernesto Oroza, gathers together objectual constructions whose conformation and referential potential are the result, in each case, of interactions of varying degree and nature between different disciplines, models and systems of cultural production. I include as examples, in an incomplete list, urban planning, architecture, sculpture, design, interior decoration, museography, essayist literature and publishing activities.

The basic regulator of these interactions is the research work and reflection that both artists have engaged in during the past few years. Established as a methodology, the expansion and enrichment of that work has been put to the test, consecutively, in the different projects implemented within its framework. We would even go further in the case of the example we are addressing: besides shedding light on some aspects of the exhibition, “Notes on the Moiré House (Or, ‘Urbanism’ for Emptying Cities)”, the text authored by both artists and included in the tabloid that accompanies Decoy, represents a moment in the development of a line of thought whose elaborations, previously disseminated, also serve as methodological support for the strategies applied in the show. Likewise, the elements and structures physically displayed in the exhibition space already form part of or are on the way to become configured as a series of conceptual and material sys- tems and tools in an ongoing process of growth that Moreno and Oroza have forged, progressively, under the principle of diagram design. Theirs are, therefore, modelizations with a high level of pragmatic capacity, adaptable to very different installation and operation situations, and with functional possibilities of use outside the field of art, ultimately their place of origin.

In terms of artistic deed, Decoy features a close relationship with the problems of the contemporary city and the ways of inhabiting it, as well as with the production processes, the con- sumption flows and the new social behaviors that characterize the latter, but I would dare say that it communicates interstitially with one of the richest trends of the European avantgarde: the one that put into circulation the notion of the link between art work production life. It is true that, setting itself apart from the celebration of technique and of social redemption that nourished the approaches to the subject elaborated by the Bauhaus and by Russian productivism, what Decoy proposes as strategy is the use of any material and opportunity available for the popular invention of alternatives to the impositions of consumerism; however, of the demythologizing impulse of artistic practice associated to this modern trend, Decoy con- serves what was perhaps its most important trait: the interest in fusing (confusing) art into (with) architecture, design and, in general, the processes of material production.

Perhaps the notion of diagram central to Moreno and Oroza’s current discursive speculations, as we pointed out before might be fitting as metaphor to represent the research exhibition project that both artists are articulating jointly. In that case, Decoy would be something like one of the components or operations of that project: a place to situate oneself inside their diagram.

(spanish version):

Farside Gallery. Miami

por José Antonio Navarrete / Arte Al Dia International, Julio 2010

Decoy, muestra de Gean Moreno y Ernesto Oroza, reúne construcciones objetuales cuya conformación y potencialidad referencial resulta en cada caso de interacciones de carácter y grado variables entre distintas disciplinas, modelos y sistemas de la producción cultural. Incluyo como ejemplos, en una lista incompleta: el urbanismo, la arquitectura, la escultura, el diseño, la decoración interior, la museografía, la literatura ensayística y la labor editorial.

El regulador básico de esas interacciones es el trabajo de investigación y reflexión que los dos artistas han desplegado durante los últimos años. Constituido como metodología, la expansión y enriquecimiento de este trabajo han sido puestos a prueba, consecutivamente, en los diferentes proyectos realizados dentro de su cauce. Diríamos más, atendiendo al ejemplo que nos atañe: “Notes on the Moiré House (Or, ‘Urbanism’ for Emptying Cities)”, el texto con autoría de ambos incluido en el tabloi- de que acompaña a Decoy, además de iluminar algunos aspectos de la exposición se inserta como un momento del desarrollo de un pensamiento cuyas elaboraciones previamente difundidas también sirven de soporte metodológico a las estrategias que se aplican en ésta. Por igual, los elementos y estructuras dispuestos físicamente en el espacio de exhibición ya forman parte de o se encaminan a configurarse como una serie en crecimiento hasta el presente de sistemas y herramientas conceptuales y materiales que Moreno y Oroza han fraguado, de manera progresiva, bajo el principio del diagrama. Se trata, en consecuencia, de modelizaciones con una elevada capacidad pragmática, adaptables a situaciones de instalación y desenvolvimiento muy diferentes y con posibilidades funcionales de uso fuera del campo del arte, su lugar de origen en última instancia.

En tanto hecho artístico, Decoy se postula en relación estrecha con las problemáticas de la ciudad contemporánea y los modos de habitarla, así como con los procesos de producción, los flujos de consumo y los nuevos comportamientos sociales que caracterizan a la última, pero me atrevería a decir que se comunica intersticialmente con una de las tendencias más ricas de la vanguardia europea: aquélla que puso en circulación la idea del vínculo existente entre arte trabajo producción vida. Es cierto que, a distancia de la celebración de la técnica y la redención social que alimentó los enfoques sobre el tema elaborados por la Bauhaus y el productivismo ruso, lo que Decoy propone como estrategia es el aprovechamiento de cualquier material y oportunidad disponibles para la invención popular de alternativas a las imposiciones de consumo; sin embargo, del impulso desmitificador de la práctica artística asociado a esa tendencia moder- na, Decoy conserva lo que quizás fuera en ella más importante: el interés por fundir (confundir) el arte en (con) la arquitectura, el diseño y, en general, los procesos de la producción material. Tal vez la noción de diagrama central para las especulaciones discursivas actuales de Moreno y Oroza, como señalamos antes podría ser apropiada como metáfora de representación del proyecto de investigación exposición que ambos están articulando conjuntamente. En ese caso, Decoy sería algo así como uno de los componentes u operaciones de ese proyecto: un lugar para situarse en el interior de su diagrama.

Contemporary artist Ernesto Oroza re-presents “Archetype Vizcaya”

By Janna Lafferty, Vizcaya Museum & Gardens Examiner April 21st, 2011.

http://www.examiner.com

There is irony in Ernesto Oroza’s title, “Archetype Vizcaya.” He is less asking his audience to uncover something original and immutable then to point to the many folds of appropriation, redefinition, hybridity, and adaptation—processes of change—that first produced and continue to reproduce Vizcaya. For Oroza, Vizcaya provokes uneasy questions about the boundaries between production and reproduction, foreignness and indigineity, and the absoluteness of originality, authenticity, and meaning. Can reinvention, simulation, and syncretism be their own archetypes? Engaging these themes, Oroza puts the eclecticism of owner James Deering’s and designer Paul Chalfin’s architectural historicism into conversation with how he sees people variously using, thus re-defining, Vizcaya today. Among them, the museum’s methods of material conservation and Vizcaya’s popularity as a venue for quinceañeras.

Ernesto Oroza is a contemporary artist and conceptual designer from Cuba, whose work has enjoyed exhibition in galleries and museums across the globe, including France, Canada, New York, Spain, and the Netherlands. His work explores vernacular appropriations of material culture. As the artist currently commissioned for Vizcaya’s Contemporary Art Project, Oroza invites visitors to revizualize Vizcaya—to see elements that largely go unseen, emphasizing its layers of appropriation and hybridity. He accomplishes that in three ways.

First, Oroza has created a “map” in the form of a fold-out brochure, which visitors pick up in the piazza of the main house. Inside, Oroza has created a cartography of otherwise obscure visual elements, creating a beautiful legend of patterns that come from the floors, terrazzos and other decorative objects throughout the house. Each snippet of visual design on the map is numbered, correlating to one of 41 rooms, so that visitors become explorers of unique visual patterns. All of them instantiate the ways James Deering and Paul Chalfin appropriated the design and art elements of particular times and places. The map itself becomes its own decorative take-home piece.

Secondly, Oroza calls attention to the plexiglass coverings that have been placed over certain elements in the home as a preservation measure. Oroza sees these as curious and invasive elements that assert new meaning and definition into this place. They are the kind of implements that transform a private residence into an institutionalized public space. On their surface, Oroza imposes his own invasion—his own subjective layers, placing silhouettes of invasive plant species known to threaten Miami’s native flora. It seems an obvious provocation of questions. To what extent do we understand “Villa Vizcaya” and its architects as invaders, bringing outside elements and planting them in the Miami wilderness?

Finally, a second-story room plays a looped video collage, cataloguing amateur videos of people who’ve set their quinceañeras and weddings in Vizcaya’s elaborate gardens–gardens that themselves simulate the renaissance garden layouts of Italy and France. By the time we are watching these families borrow Vizcaya and make it their own, we have a sense of how the inventors of Vizcaya did the same. The meanings attached to Vizcaya become layered and fluid, a place of pronounced bricolage in city of tremendous flux.

Ernesto Oroza’s installation continues through May 29th, as part of Vizcaya’s ongoing Contemporary Arts Project (CAP). CAP was established as a way for the museum to connect with the national and local art community, extending invitations for notable artists to interpret Vizcaya’s space and resources. The museum invites two artists to present work in and about Vizcaya annually, which is exhibited over several months. Flamina Gennari-Santorni works with a select committee of national curators to elect the artists recruited for commission in a given year. The project helps to make Vizcaya a living, evolving social space. Oroza’s work especially demands self-reflexivity, not only emphasizing how the museum’s efforts to preserve a history itself creates and is created by its present, but that tensile relationships always mark that existence. To be living means always grappling–but, hopefully, not becoming complacent–with paradox.

Mapping Vizcaya

Written By Anne Tschida APRIL 2011

Biscayne Times

IN HIS LATEST WORK, CUBAN ARTIST ERNESTO OROZA NAVIGATES THE FAMED ESTATE’S HISTORY, BOTH REAL AND IMAGINED

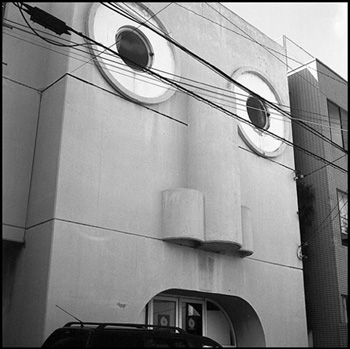

Visiting Vizcaya Museum and Gardens is a quintessentially Miami experience. The view of Biscayne Bay is spectacular. The gardens are lush and tropical. And the interior design of the faux Italianate villa is so over-the-top, so wannabe A-list as to be, well, so Miami.

The house was built by one of South Florida’s first transplanted tycoons, a product of the Gilded Age, James Deering. He wanted his mansion to look as though it had been around for centuries, like a real Old World landmark. So in 1916 he had his designer, Paul Chalfin, appropriate a mish-mash of styles from the 16th to 20th centuries for the new structure.

James Deering, a Gilded Age tycoon, found Miami to be the perfect place for his visions of faux grandeur. Photos courtesy of Vizcaya Museum and Gardens.

In 1953 this quixotic specimen of grandeur and excess — really, a Disneyfied version of a European castle, years before anyone had even heard of Uncle Walt — became a museum, run to this day by Miami-Dade County.

This history, simultaneously real and imagined, organic and borrowed, captivated Ernesto Oroza, a Cuban-born artist who spent a year walking the museum. The more he walked, the more he noticed the quirky secrets of the villa — on the floors, the walls, and even in the mix of visitors flowing in and out. Oroza eventually came up with Archetype Vizcaya, the latest in the Contemporary Arts Project series commissioned by the museum.

Oroza has literally mapped out the normally unseen highlights of Vizcaya in an artful brochure, which includes a legend with numbers and symbols. On a sunny, cool day, he points out some of his explorations.

When he first started making his rounds, he says, he noticed what was constantly under his feet: the floors made of marble, terrazzo, wood, tile, different styles all shoved together, sometimes in a single room. In particular it was the marble that really caught his eye. It is, he explains, the ultimately “contaminated” material. Over thousands of years, minerals and weather have infected the stone, imposing on it that unique quality of veins running through it. “To mineralogists, these shapes that we consider beautiful are, in fact, impurities that invaded the rock,” Oroza explains. “Any piece of marble in Vizcaya may be considered the diagram of a similar process of contamination that has occurred during the life of the building.”

And, he adds, marble shouts out wealth, another central theme of Vizcaya. From ancient times until today, marble columns, sculptures, and especially floors have signaled to visitors that money and power inhabit a space. And Vizcaya is covered in it.

Modeled on 17th- and 18th-century Venetian floors, the marble layerings in the villa were imported, likely from North Africa, another way for moguls like Deering to flag wealth “and worldly experience,” says Oroza. “It was from the beginning meant to be a showroom.”

Vizcaya was designed in the era of Cecil B. DeMille, and any resemblance to a larger- than-life movie set is intentional.

As you move from room to room with Oroza’s map, you see the beginnings of Miami as a place where outside influences and manufactured identities dominate. We reinvent ourselves here all the time. “History” is malleable. Pasts are remade or just erased.

Take the Breakfast Room. It is decorated in a pseudo-Chinese style, popular in the late 19th Century, with lacquered furniture (actually crafted by a Cuban team) and a painting of a South China Sea fishing scene (actually painted in the late 1600s by a Frenchman). As the new deputy director for collections and curatorial affairs, Flaminia Gennari-Santori, who is overseeing the art series, quips: “Look closely. One of the fishermen was really born in 1916!” The original painting was expanded to fit the wall, which meant adding figures and subjects. Talk about imposition and contamination.

Other stops on the map reveal subtle points that would go unrecognized without some help from Oroza, such as details in the 550-year-old rug depicting the “Hand of Fatima.” Oroza’s own interventions are few, and are pasted on Plexiglas barriers in certain rooms: silhouettes depicting invasive plants that have been imported to Miami through the years, endangering the native vegetation. The Plexiglas itself is its own, strange intervention, says Oroza — something that jumped out at him, like the floors. When the villa became a museum, these Plexi plates were installed to keep visitors from harming valuable objects or venturing too deep into the rooms. But as Oroza points out, they were haphazardly placed, in some cases protecting relatively unimportant works, while other more precious pieces stood completely exposed.

A third segment of this unconventional art exhibit involves Oroza’s “mapping” of the people who have passed through Vizcaya over the past half-century. Using the Web, he gathered amateur videos of quinceañeras, weddings, parties, and star-studded concerts, which unspool in a continual loop (Oroza adds to it when he can) in the South Gallery. This study of human interventions at the site leads him to understand something else about Miami. As a relatively recent arrival from Cuba, Oroza says he had never visited the museum. But once he started hanging out, he saw how central the place has become to the local Cuban community, another important layer in Miami’s multilayered history.

From Deering to Chalfin, from the property’s African and Japanese plant species to exile families celebrating coming-of-age rituals — and even the hands behind this exhibit (the Cuban Oroza and Italian Gennari-Santori) — Vizcaya reflects so many of the influences that make up the broader cultural terrain here.

Oroza has devised a clever way to uncover all this. As Gennari-Santori writes in the exhibit’s introduction: “The map directs us to look at the surfaces beneath our feet and, in doing so, breaks our normative viewing habits and frees us to participate in an intensive treasure hunt for curious artifacts. Oroza’s map is an object in its own right that can be taken home and enjoyed as a piece of art or wallpaper, or in any way one wishes.”

Archetype Vizcaya is a highly conceptual work from a very intellectual mind, but it can be engaged on almost any level. If you’ve never been to this amazing museum, here’s your excuse; follow the map through the house, or just take the opportunity to wander and stumble on some interesting tidbits.

Oroza gathered amateur videos of parties, weddings, and galas held at Vizcaya, which unspool in a continuous loop.

Circling back to the idea that Vizcaya was, from its inception, supposed to be a showroom, Oroza points out it was designed in the era of Cecil B. DeMille, and any resemblance to a larger-than-life movie set is intentional. “It was made to be photographed,” he says. “It was made to be catalogued.” And of course it was made to be explored.

A progress report on the ongoing renovations at Miami’s Vizcaya Museum…

By Beth Dunlop Special to The Miami Herald, 2011/04/10

Vizcaya’s entrance loggia with its interesting floor is on the explorer’s map of the estate that Ernesto Oroza devised as part of his art project, ‘Archetype Vizcaya.’

Ernesto Oroza’s new contemporary art project, Archetype Vizcaya, is a puzzle and a treasure hunt. It’s part of a series that offers artists the opportunity to look at Vizcaya through a unique contemporary lens, a chance to interpret, intervene or even invent: temporary new work — some of it extremely conceptual — layered over aging beauty. As such, Oroza’s work offers an enlightening new way to look at and learn more of an extraordinary and complex house built by James Deering, the heir to a giant farm-equipment fortune, and completed in 1916. Archetype Vizcaya offers a perfect metaphor for the moment, for place and time.

Vizcaya Museum and Gardens is one of this country’s most important historic houses — for its architecture, decorative arts and gardens — and among the most beautiful. It is also one of the most complex. Almost every element bears scrutiny and understanding, and only now are its curators and caretakers beginning to unlock its many secrets.

In many ways, Vizcaya is at a turning point. Just five years shy of its centenary and almost six decades after it be came a key part of Miami-Dade County’s cultural holdings, it is getting a fastidious, piece-by-piece examination and — where needed — restoration. The magnificent Sutri Fountain at the far edge of the garden and long called the Rose Garden Fountain, has just been restored (by Conservation Solutions, Inc.), along with the important, and delightful, garden sculpture surrounding it.

The café and gift shop, much damaged in 2005 during Hurricane Wilma, are renovated (by R.J. Heisenbottle Architects) and will reopen in June. The David A. Klein Orchidarium just outside the café and grotto swimming pool is being returned, by the landscape architects Falcon + Bueno, to a condition more like its original so that a small lawn fringed with ornamental plants yields to a hammock. Two of the quaint Vizcaya Farm Village buildings across the street have been restored, also by Heisenbottle. A cultural landscape report (by Heritage Landscapes) that documents the historic horticulture of the gardens has just been completed.

Within weeks, possibly sooner, design work will begin to replace the heavy-handed black-metal glass space frame roof that covers the courtyard, a legacy from the 1980s. The archives have been organized — for the first time ever — and, even more important, each painting, sculpture, rug, chandelier, sconce, fitting and piece of furniture is being studied and catalogued. Last fall, Vizcaya introduced an audio tour in English and Spanish, which enables visitors to wander knowledgeably at their own pace.

And, from now through May 29, there is Ernest Oroza’s magical map to follow. The map comes in the form of a fold-out brochure. Open it, and there are numbered icons drawn from patterns in the exquisite, intricate floors. The icons in turn relate to 41 different rooms in Vizcaya and, sometimes, to particular objects, forcing the visitor to seek out patterns in the floor and hidden images and iconography in the furniture and architecture. In this engaging and enigmatic work, past is prologue, and the present is multi-layered.

The map is just part of the project. Oroza also has added a layer to certain rooms, Plexiglas panels with designs that pose the question of what’s authentic and what’s not — appropriate in a house in which most of the furnishings and fittings were antiques bought in Europe and shipped to what was, in 1916, still an outpost of civilization in the New World, with some pieces reassembled for uses far from their original intent. Oroza wants us to think about these issues, then take our observations even further.

His project ends in a makeshift gallery where a continuous video loop shows some of the ways that Vizcaya is used now — most particularly in footage of girls bedecked in gowns posing for their Quinceañera photos. All of this is heady and intelligent and, at the same time, capricious and full of joy.

Oroza’s fascination with the balance between a venerable historic house and its perception (and use) by the larger public points up some universal truths, most fundamentally that humans are drawn to beautiful places and spaces and when something like Vizcaya can be theirs — even for a moment — they make it so. A century, a culture and much more separate James Deering from the 15-year-olds in the Quinceañera photos, and yet both have borrowed from the grandeur of another era to make it their own. In Deering’s case, the borrowing was for a lifetime; today, often, it is for the hour spent shooting a portrait.

Oroza wants us to think about this. Follow his map, follow his path, watch the videos, and you will.

The Contemporary Art Project is funded by foundation grants and private donations. Artists are selected by a prestigious jury, most of them curators from widely regarded museums across the country, in conjunction with Vizcaya’s deputy director for collections and curatorial affairs, Flaminia Gennari-Santori.

“We’re not a contemporary art institution,” she says, “but we see this as a way to reinforce ourselves. The context here is so strong that it can create a way of re-thinking.”

Gennari-Santori. and Vizcaya’s director, Joel Hoffman, have Ph.D.s in art history and are dedicated stewards of the rich treasure that is Vizcaya, and they also fully understand that dichotomy between the once-private, grand mansion of one of this country’s richest men and the public museum that it is today, preserving the all-important work of its architect, F. Burrall Hoffman; designer, Paul Chalfin, and landscape architect, Diego Suarez, and paying homage to their collective brilliance. Even more, they are public stewards of a building and collection of enormous scholarly and aesthetic importance — and learning . Theirs is a rigorous and daunting task.

The magnificent Sutri Fountain, for example, had been installed incorrectly in 1920 (Gennari- Santori. suspects that the workmen confused inches and centimeters) and thus always leaked. Restoration involved not just cleaning it but also removing and re-setting it to fit. The fountain, which Deering and Chalfin bought from an antiques dealer in Rome in 1916, had been in the piazza in the small Italian town of Sutri, just north of Rome, and was most likely was designed in 1722 by Felippo Barigioni whose other work included the fountain in the Piazza de Pantheon in Rome.

This detailed level of scholarship importantly provides a basis for understanding not just a specific piece but also the whole intricate interrelationship between house and garden, furniture and art. Moreover, it provides a base line for restoration work and for decision-making — for example, in the refurbishment of the storm-damaged café.

In the café and gift shop, which have been operating from a tent, diners and visitors will get a glimpse (woven wicker, dark wood, leaded glass) of what would have been Deering’s gaming and smoking rooms and can see some details of the original (sconces, rails, marble), but the rooms are more or less a necessary adaptation to a new use. Peer through the windows to see the grotto pool (look, but don’t swim) which has seamlessly gotten new flood-control engineering.

Time and wear, weather and climate all play into the decision making about Vizcaya’s future — that delicate balancing act. After Hurricane Wilma’s damage, Hoffman convened a charrette to look at alternatives to the almost 30-year-old glass canopy over the Vizcaya courtyard. Several options were explored — among them a glass wall dividing the courtyard from the house, a lower glass “ceiling,” the zoning of the house to air-condition rooms — under the theory that technology has advanced enough to allow for a more minimal and elegant solution than the ugly black space frame. Ultimately, the simplest of alternatives emerged: replacing the roof with a lighter, closer-to-invisible glass roof. It’s a much-needed step, and a critical one, paying homage to the real architecture once again.

In the meantime, there’s an entirely absorbing and entertaining way to look at Vizcaya — through an artist’s eyes and through your own. It’s a testament to the power of Deering and the men who created this remarkable house and gardens that it is all, always, a discovery, be it new scholarship, restoration revelations or simply the product of close examination. What’s clear is that going forward into its second century, Vizcaya is in good hands — cherished and honored and celebrated. And cared for and conserved. What more can we ask?

Villa Vizcaya transfigurada: entre la quimera y el diseño

Janet Batet. El nuevo Herald, Publicado el domingo 17 Abril del 2011

Como parte del programa Contemporary Art Project (CAP), el Museo de Vizcaya presenta hasta el 29 de mayo, Archetype Vizcaya, proyecto del artista cubanoamericano Ernesto Oroza.

En Archetye Vizcaya Oroza creó una cartografía que transfigura la mirada del visitante proponiendo una nueva lectura de la famosa villa italiana en Miami.

Para el proyecto, Oroza escogió el plexiglás como elemento central por dos motivos esenciales. La primera, histórica: cuando la villa devino museo en 1953, las láminas de plexiglás funcionaban como frontera limítrofe que delimitaba el espacio y los objetos exhibidos de los visitantes; segundo, por ser el plexiglás el material más contemporáneo empleado en la construcción del edificio.

Las láminas de plexiglás devienen estructura arquitectónica provisional, pobladas con la silueta de plantas consideradas hoy “invasivas” que, posiblemente, hayan sido introducidas en la Florida por James Deering, dueño de Villa Vizcaya, y que actúan a un tiempo como elemento decorativo e interferencia en el proceso perceptivo.

Construida en el mismo momento en que se elevaban los rascacielos de Nueva York y Chicago, Villa Vizcaya contrasta como poder simbólico escapista que mira a Europa y al pasado. En este sentido, Oroza sustantiva el extendido uso del lugar como mero decorado y quimera para ocasiones como es el caso de las populares fiestas de quinceañeras.

Ernesto Oroza. Viscaya Museum and Garden, Miami

by Janet Batet. Arte al dia International

As part of the Contemporary Art Project (CAP) program, the Vizcaya Museum presented “Archetype Vizcaya”, an exhibition by Cuban-American artist Ernesto Oroza.

Ernesto Oroza is well known for his incisive commentaries on contemporary urban culture. With a background that includes deep conceptual roots and a solid training in design, Oroza appropriates a space or an aspect of the urban environment and, through a deconstructive process, he returns the object he has manipulated entirely transfigured.

In the specific case of “Archetype Vizcaya”, the artist explores the shift in meaning which has its point of departure in the de-contextualization and redirecting of the gaze. To this end, Oroza created a “provisional space” delimited by Plexiglas panels that function as a “parallel” structure within the museum’s architecture. There are two essential reasons behind the choice of Plexiglas as a central element in his work. The first is of a historical nature: when the villa became a museum in 1953, the Plexiglas panels functioned as a frontier that kept the space and the objects exhibited separated from visitors.

The second reason, associated to the synthetic nature of the material, imposes an essential contrast with the rest of the build- ing which stands out for its escapist vocation. Built at the begin- ning of the 20th century − coinciding with the start of construction of the New York and Chicago skyscrapers − the marvelous villa stands out for its evasive character, revealed by its appropriation of 16th century Italian Renaissance architecture at a time when architecture and design opted for technological advancement and the incorporation of ultra-modern materials. Oroza sets his use of Plexiglas against the use of marble as an invasive and contaminating element. As the artist rightly points out, marble is “the result of a process of contamination of limestone rock by a flow of magma.” Based on this concept, Oroza devotes himself to a compilation of all the invasive processes the villa has been subject to throughout its one hundred years of existence. Within this process, he highlights the inventory of “invasive” plants from the most remote confines that populate the villa and emphasize the notion of escape that distinguishes the venue. From this detailed classification, Oroza utilizes the formal element. The leaves, reduced to silhouettes, invade the crystalline surfaces of the Plexiglass, acting at the same time as decorative element and interference in the perceptive process. “Archtype Vizcaya” is accompanied by a map in which Oroza reveals historical details of interest, articulating the building’s dual function. Since while the complex was conceived as a summer house commissioned by James Deering, its designer, Paul Chalfin, cleverly used it for his own self-promotion, transforming the mansion into his own personal

portfolio.

To illustrate this “parasitic” use of the building, Oroza draws attention towards the extended utilization of the place as a mere décor and chimera for the popular fifteenth birthday celebrations, reducing the complex − in the same way as Chalfin did − to a décor for personal purposes. To emphasize this effect, the map-catalogue created by Oroza fulfills a double function. On the one hand, the fundamental one of guiding the visitor in this unusual tour of the Vizcaya Museum; on the other hand, there is the mere decorative character. The symbols used at the back − as an indication of the language employed − become a mere ornamental pattern, in such a way the catalogue displayed on the wall may be used as a decorative wallpaper.

“Marble is a material that results from the encounter of powerful natural forces; colored veins are the result of a fluid of magma that penetrates the limestone rock. To mineralogists, these shapes that we consider beautiful are, in fact, impurities that invaded the rock. Any piece of marble in Vizcaya may be considered the diagram of a similar process of contamination that has occurred during the life of the building.

Similarly, for almost a century, Vizcaya has been exposed to the pressures of individual, social, economic and institutional forces, in an ongoing process of contamination. One of the most powerful and pervasive of these forces was Paul Chalfin (1873-1959), the artistic director who created Vizcaya’s fantastic interiors twisting and playing with the canon of European decoration. Other major transformations occurred after 1953, when Vizcaya became a museum. For example, to protect artifacts from visitors panels of plexiglass were placed over many surfaces. It was as if a transparent plastic vein had invaded the stone body of the building. Vizcaya itself can be seen as an intrusion into the Miami tropical landscape of 100 years ago.”

Ernesto Oroza, 2011

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 Map (Front)

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 Map (reverse)

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 The Video Archive (espacioprovisional.info/vizcaya): This archive is a compilation of videos filmed by visitors in the exteriors of Vizcaya and posted on YouTube. They include quinceañeras, weddings, tourists, parties and concerts.

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 Map, installation

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 The Video Archive (espacioprovisional.info/vizcaya): This archive is a compilation of videos filmed by visitors in the exteriors of Vizcaya and posted on YouTube. They include quinceañeras, weddings, tourists, parties and concerts.

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011. Preparatory drawings

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 Installation view

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

- Archetype Vizcaya, 2011 “Espacio Provisional/ Provisional Space: The plexiglass panels that cover and preserve surfaces throughout Vizcaya constitute a gallery I call Espacio Provisional. To show the “architecture” of Espacio Provisional, I use the plexiglass as an exhibition space. On several of them, I have placed a grouping of vinyl silhouettes that represent invasive plants prohibited in Miami-Dade County.”

Notas sobre Espacio Provisional *

Espacio provisional en Vizcaya asume como su estructura física y espacial las láminas de plexiglás que fueron colocadas en 1953 cuando la casa devino museo para proteger el lugar y los objetos de los visitantes. En mi proyecto considero estos plexiglases una superficie expositiva paralela al museo. El plexiglás es, posiblemente, el material más contemporáneo con el edificio, fue inventado en la misma década que se construyó Vizcaya, específicamente en 1928.

Para esta primera exposición decidí organizar sobre estos plexiglás una muestra que cumpliera tres funciones:

1- Indicar cual es la superficie de Espacio Provisional en Vizcaya, esta función articula y describe estas láminas como una estructura arquitectónica expositiva. Esta función puede ser considerada arquitectural.

2- Documentar practicas invasivas y contaminantes. En el texto del mapa hablo del mármol como el resultado de un proceso de contaminación de una roca caliza por un fluido de magma y lo propongo como un diagrama del Vizcaya, el cual ha albergado procesos similares de contaminación y apropiación durante sus 100 años.

Seleccioné un conjunto de plantas invasivas listadas en el website del condado Miami-Dade. Todas provienen de lugares remotos como Asia, África, Brasil, Mediterráneo.

Deering, dueño del palacio Vizcaya, pudo haber sido el precursor de la entrada de estas plantas decorativas e invasivas en la Florida. Con estas siluetas blancas de plantas invasivas sobre los plexiglases se produce un proceso de omisión de la textura barroca del Museo. En este sentido, la metáfora del mármol va mas lejos, al homologar las plantas invasivas que atraviesan las superficies de Vizcaya con las vetas de magma que atraviesan la roca caliza.

3- La tercera función es decorativa. Se activa con la colocación del patrón de plantas invasivas por cada área del museo al integrarse a la textura decorativa de Vizcaya. Es decir, el proceso de documentación sistemático termina por generar un patrón que puede eventualmente cumplir una función decorativa. La repetición documenta-representa el carácter expansivo de estas plantas. De alguna forma la escala que usé hace participar esta muestra como una intervención de diseño interior. Ambas cosas, el “documental decorativo” y el interior como una estructura para relacionar elementos de una investigación son procesos que empecé en Cuba con la muestra personal que hice en la Fundacion Ludwig, 2005.

*Espacio provisional es un proyecto expositivo fundado en Cuba para realizar exposiciones independientes, algunas de las cuales solo duraban un día. He adpatado el proyecto a EUA participando en Milwaukee Internacional Art Fair en el (2008), Dark Fair, Swiss Institute NY (2008), “No Soul For Sale – Festival of Independents,” Tate Modern, London (The Suburban/Milwaukee International) (2010) entre otros.

Una segunda exhibición para Espacio Provisional en Vizcaya fue planificada pero no realizada.

Notas sobre el Mapa

El mapa cuenta con una tirada de 5000 ejemplares por cada idioma english/spanish.

Durante mis primeras visitas al museo noté que Chalfin, el diseñador, había hecho un uso astuto de su proyecto en Vizcaya, la lejanía geográfica del lugar en ese momento y un uso eficaz de la prensa especializad (Harper Bazar, etc) y de fotógrafos le permitió promover su trabajo de diseñador de interiores en busca de nuevos clientes. Es decir, Chalfin creó un set fotográfico, un espacio altamente fotogénico, que no podía ser puesto en cuestión sin una visita al lugar, algo difícil pues estaba muy lejos de las grandes ciudades. El edificio tiene esa doble agenda, por un lado es el hogar veraniego de Deering, el cliente, por otro es el portafolio personal mas exuberante para un diseñador de la época.

El mapa que hice favorece esa inercia de mostrar, exponer, articulándose como un display minucioso de los pisos de Vizcaya mientras que deja ver secretos, objetos y obras de la colección e inventos de la época (el Vizcaya se construía al mismo tiempo que crecían los rascacielos de NY y Chicago y es producto de la presencia paradójica de alta tecnología y de un afán historicista coartado por el cine épico de Hollywood y las grandes superproducciones de D.W Griffith)

Flaminia me comentó, al inicio del proyecto, que las quinceañeras como parte de la negociación de la renta para las fotos reciben un ticket para regresar al lugar a manera de visita guiada y jamás ninguna regresó con ese fin. De alguna forma este comportamiento extiende el uso astuto y pragmático de Chalfin el diseñador de interiores. La familia considera Vizcaya una imagen de fondo, una superficie optimizada simbólicamente y así puede verse en lo videos en los cuales se muestra un reconocimiento formal de escaleras, paseos, esculturas que valorizan sus escenas pero no parece producirse una asimilación vivencial del lugar.

Decidí entonces añadir un elemento en el reverso que pudiera ser tomado para producir estos “fondos” en los hogares de Miami. El mapa puede ser tomado en el lugar y configurar decoraciones, doilies, etc. Con el mapa recupero el proceso Documental decorativo: el reverso, además de documentar un piso ficcionado del Vizcaya puede ser empleado como un patrón decorativo.

- Seaside Mahoe (Thespesia populnead)

- Puncture Vine (Tribulus cistoides)

- Napier Grass (Pennisetum purpureum)

- Melaleuca quinquenervia

- Day Blooming Jasmine (Cestrum diurnum)

- Climbing Fern (Lygodium japonicum)

- Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

Prohibited Plant Species List

The following is a list of plant species prohibited in Miami-Dade County.

- Air Potato (Dioscorea bulbifera)

- Australian Pine (Casurina equisetifolia)

- Banyan Fig (Ficus benghalensis)

- Bishopwood (Bischofia javanica)

- Brazilian Jasmine (Jasminum fluminense)

- Brazilian Pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius)

- Burma Reed (Cane Grass) – Neyaudia reynaudiana

- Carrotwood (Cupaniopsis anacardioides)

- Castor Bean (Ricinus communis)

- Catclaw Mimosa (Mimosa pigra)

- Climbing Fern (Lygodium japonicum, Lygodium microphyllum)

- Day Blooming Jasmine (Cestrum diurnum)

- Earleaf Acacia (Acacia auriculiformis)

- Gold Coast Jasmine (Jasminum dichotomum)

- Governor’s Plum (Flacourtia indica)

- Indian Rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo)

- Lather Leaf (Colubrina asiatica)

- Lead Tree (Leucaena leucocephala, Leucaena glauca)

- Lofty Fig (Banyan Tree) – Ficus altissima

- Laurel Fig (Banyan Tree) – Ficus microcarpa, Ficus nitida, Ficus retusa

- Mahoe (Hibiscus tiliaceus)

- Melaleuca (Punk Tree) – Melaleuca quinquenervia, Melaleuca leucadendron

- Napier Grass (Pennisetum purpureum)

- Puncture Vine (Tribulus cistoides)

- Queensland Umbrella Tree (Schefflera actinophylla, Brassaia actinophylla)

- Red Sandalwood (Adenanthera pavonina)

- Seaside Mahoe (Thespesia populnead)

- Shoebutton Ardisia (Ardisia elliptica, Ardisia humilis)

- Tropical Soda Apple (Solanum viarum)

- Woman’s Tongue (Albizia lebbeck)

- Woodrose (Merremia tuberosa)